For as long as I can remember I have been fascinated by

Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” My

parents never had their own house so they, my two brothers and I all lived in

my grandmother’s house. My parents didn’t keep a lot of books, but I remember

that in the living room on a shelf above the bureau there were some red

hardbacked copies of famous novels. There weren’t a huge number of them. I can

remember there being David Copperfield, The Mill on the Floss, Jane Eyre, Pride

and Prejudice, Wuthering Heights, Little Women and Alice’s Adventures in

Wonderland (and Alice through the Looking Glass).

These books, the look of them with the gold lettering on their faded red cloth spines, fascinated me from a very early age. My grandfather had bought them. They were in fact published by Odhams in the early 1930s. I can't categorically say that I can trace my love of books back to them, but they played their part.. When I was first becoming interested in things around me, the only one I could even try to read was “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass”. It helped that Alice had illustrations. At that tender age I didn’t really get much of the story, and some of the pictures frightened me. But then, kids do like to be frightened to an extent. Later on I would identify these as the Tenniel illustrations - but they were not! As one of life's little ironies the book also contains Thackeray's The Rose and the Ring. Thackeray's Vanity Fair is my favourite novel.

As I grew up I came to love Victorian illustrations and

cartoons and those by Sir John Tenniel in particular. A few years ago I

challenged myself to make copies of all of his original illustrations of Carroll’s

Alice books. When I’d finished copying all 92 of them then I became interested

in the ways that certain other artists and illustrators had chosen to depict

scenes from the stories. I came upon an illustration of Alice with Humpty Dumpty

by an artist called E.B.Thurstan. It was published in 1930. Frustratingly I was

able to discover nothing about the artist. But I loved the original of it, and

was struck by how it seemed to draw on Tenniel’s original.

For quite some time I didn’t think any more about this. But

then I began obtaining copies of the Alice books illustrated by my favourite

Alice illustrators – namely Tenniel, Mervyn Peake, Arthur Rackham, Ralph

Steadman, Charles Robinson and Harry Rountree. It seemed a nice idea to also

get hold of a copy of the Odham’s edition that had introduced me to the stories

as a kid. What do you know? It turned out that this edition did not use the

Tenniel illustrations at all. Edgar

Thurstan had in fact produced the illustrations in the Odhams edition of the

Alice books that I remembered from when I was tiny. Thurstan only produced 21

illustrations for the two books in total.

Not all of Thurstan’s illustrations seem to draw so heavily

on Tenniel as others do. For example, Thurstan illustrated Alice falling down

the rabbit hole, which Tenniel never did. But with a fair number of them the

debt to Tenniel is quite striking. To me, it’s so obvious that there’s no way

that it can have been unintentional. There’s no way of finding out for certain

just how this came about, but I reckon it probably boils down to one of a

couple of explanations, namely

* Perhaps Odhams liked the iconic Tenniel originals. However they

were still in copyright. Rather than pay the Tenniel estate to license them,

maybe they instructed Edgar to make a set of illustrations which were as close

as possible to Tenniel in terms of style and composition without infringing

copyright.

* Edgar himself decided with many of the illustrations to start with the Tenniel originals and use them as the basis for a significant number of his own Alice illustrations, maybe through lack of inspiration, maybe out of some sort of homage to Tenniel.

How similar is Thurstan’s work to Tenniel’s, then? Well, let’s start with my copy of Thurstan’s illustration of Alice falling down the rabbit hole.

This may seem a bit of a strange place to begin considering that Tenniel never illustrated Alice falling down the rabbit hole, which has always struck me as something of an omission. But actually I think it’s a great place to start, Because although there’s no composition to compare it with, the style does bear similarities to Tenniel’s. I’m thinking particularly of the use of shade and shading in the background. But also there’s Alice. Her facial features are different from Tenniel’s Alice, but she’s wearing a dress which is the same as Tenniel’s Alice in all of the significant details.

Thurstan’s depiction of the frog and fish footmen is a

great example of Thurstan’s method when producing his own take on the Tenniel

originals. In all of the following comparison’s my copy of Thurstan is on the

left, while my copy of the same scene illustrated by Tenniel is on the left.

Thurstan gives us almost a mirror image of Tenniel. The figures positions are reversed. Yet the poses of the two footmen are extremely similar in both. As are the buildings that the frogs are standing in, with the trees behind. The costumes are extremely similar. We can also see one noteworthy difference that can be seen in many of Thurstan’s other illustrations for the Alice books. Tenniel presents the characters almost as if they are on stage and we, the viewers, are the audience, on eye level with them. Edgar has us looking slightly down upon the characters and at a angle, almost from the position of a fly on the wall. We can take this point even further if we look at one of the illustrations from Looking Glass.

Here Edgar doesn’t give us a mirror image, as all the characters are in the same relative positions in both, which only serves to highlight the similarities further. Again, with Tenniel we are looking directly side on from the same level as the characters. Again with Thurstan we are looking down on the characters from an angle. But more than that, the ‘camera’ has zoomed out a little, giving us a deeper shot which shows an extra pair of legs on the left, next to the goat, and a horse’s head on the right. While Edgar often sticks to the style of dress that Tenniel uses for the characters, to my mind his guard looking in through the window looks distinctly more 1930s than Tenniel’s. Aso the man in the newspaper hat looks far less like Benjamin Disraeli than Tenniel’s does, which is hardly surprising since Disraeli had been dead for about half a century when Edgar made his illustration. Such small details aside, though, the similarities between these illustrations are staggering and must have been intentional.

I also feel that the similarities between Tenniel’s

illustration of Alice dancing with the Gryphon and the Mock Turtle can only

have been intentional.

Thurstan’s Alice mirrors Tenniel’s but the other figures seem to have been rotated clockwise around the page by about a quarter turn. In a way we can forgive Thurstan for depicting a Mock Turtle that is so similar to Tenniel’s, because he certainly wasn’t the only person to do this and he certainly wasn’t the first. Just looking at some of my favourite Alice illustrators, Arthur Rackham, Thomas Heath Robinson and Harry Rountree all did something very similar to Tenniel’s Mock Turtle and they all illustrated the books before Thurstan did. What is interesting is just how differently Thurstan depicts the Gryphon. Tenniel’s is essentially a heraldic gryphon. Thurstan’s does not have the same distinctive ears – it doesn’t have any ears at all. It does, to be fair have the tail of a heraldic gryphon, but its wings are much larger than Tenniel’s. It also seems to me that although this is one of Thurstan’s illustrations where, like Tenniel’s, the viewer seems to be looking at the characters from eye level, it is almost as if he has ‘zoomed out’ a little so we get more of the background, in particular the distinctive rock on the extreme right that just slightly resembles Durdle Door. That in itself puts me in mind of Tenniel’s illustrations of the Walrus and the Carpenter which show some recognisable cliffs in the background.

If we compare Thurstan’s illustration of the Duchess’

kitchen in the ‘Pig and Pepper’ chapter you can see some interesting things

going on.

With the Thurstan illustration we are looking down from an angle again. Alice is in a mirrored position to the Tenniel illustration, standing at the extreme left and looking to the right. However, everything else is in a very similar position relative to each other as in Tenniel’s allowing for the different viewpoints the viewer looks from. This is understandable. From this viewpoint he simply couldn’t show the cook on the right – she’d either be out of shot, or dominating the foreground. Thurstan’s Duchess wears a much simpler headdress, although its shape is similar. However, look at the extreme similarity between their facial features. And for that matter, the nearly identical faces of the screaming babies. What I particularly like about Thurstan’s illustration is the way that his very clever use of shading depicts the light coming off the oven, an effect that you don’t get in the Tenniel.

It's interesting to speculate why there are some

differences where we find them. Look at Thurstan’s Tweedledum and Tweedledee,

compared with the equivalent Tenniel illustration.

Now, allowing for the fact that this is a mirror image, seen from slightly above and rotated towards the right hand side, the similarities seem fairly clear. Yet look again at the figures. The Alices are both dressed in almost identical mid Victorian pinafore dresses. Yet while Tenniel’s Tweedles are wearing contemporary ‘skeleton suits’, Thurstan’s are wearing blazers, ties, waistcoats and trousers of the sort public schoolboys of the twenties and thirties would have done. It’s just that little bit inconsistent and one can’t help wondering what thought processes led to him making the decision to depict them in this way.

An even more obvious change can be seen in the

illustrations both men made of the scene where Alice seeks advice from the

caterpillar.

In this case Thurstan’s is not so much a mirror image, as Tenniel’s composition rotated through 180 degrees. Once you realise this the two images are a lot more similar than they appear to be at first glance. However it can be hard to get away from the differences between the two caterpillars. Thurstan makes no attempt to give us a rotated version of Tenniel’s caterpillar. For one thing, Thurstan gives us a hairy caterpillar. Where Tenniel doesn’t show us the caterpillar’s face, Thurstan does, and in my opinion it’s a little bit crude and cartoonish.

Thurstan was sometimes in a position where he had to

improvise where Tenniel had the luxury of making two illustrations of a scene,

while he could only make one. Let’s look at images illustrating Wool and Water.

Again, while Tenniel has us looking at the scene straight on, Thurstan moves the viewpoint upwards, while rotating clockwise. The two sheep are extremely similar, while the objects hanging down from the counter in Tenniel’s are conspicuously placed on the front of the counter in Thurstan’s. However Tenniel also depicts the ewe and Alice in the rowboat in a separate illustration. Not having a second illustration with which to do this, Thurstan shows an open doorway where Tenniel depicts the shop window, and through the doorway we can see the actual rowboat.

Another good example of Thurstan having to work to covey in

one picture what Tenniel has done in two comes from “Alice Through The Looking

Glass.”

Tenniel uses two images on opposite sides of the page, so that you see the back of Alice climbing through the mirror and when you turn the page you see Alice emerging into what is a mirror image of the previous picture. It’s really clever and highly effective. Edgar can only show us Alice merging into her own reflection. There are big differences, apart from the difference in viewpoint from which we observe the scene. For one thing Thurstan’s mirror is a lot more ornate and interestingly shaped. Again he has zoomed out a little so we see the whole of the mantelpiece. Yet speaking of the mantlepiece Edgar chooses to depict a dome clock immediately to Alice’s right, just as Tenniel does, and a vase immediately to her left. Tenniel’s vase has a dome on it, while Thurstan’s doesn’t.

If you look at the next pair, you might feel that they don’t look much like each other at all. Look again though. Thurstan’s Haigha (Hare) and Hatta are not foregrounded in the way that they are in Tenniel’s equivalent illustration. We’re drawn to the lion and unicorn figures, which are obviously pretty different. Tenniel’s has no unicorn in his illustration. His lion is all in shade, taking away our attention from him while it backs away, yet Thurstan’s is leaning forward into the attack.

You may be struck by the similarity of Thurstan’s Haigha and Hatta to Tenniel’s. It’s an even more striking similarity if you reverse one of the images – I’ve used the appropriate sections of the originals in this case, and reversed the Thurstan. Just in case anyone still thinks the similarities are unintentional. Now, consider that I have reversed the image. Yet the writing on the hat in the Thurstan image on top is the right way round! Suggesting that maybe Thurstan did use some kind of mirror to help him when making mirrored images of Tenniel characters.

Maybe this wasn't just a mistake - maybe Thurstan is subtly reminding us that we are in Looking Glass world. To be honest the jury is out. But it's the kind of thing which I find frustrating about Thurstan's work. Take out Haigha and Hatta and you have an original interpretation of the Lion and Unicorn episode. There is no necessity to use Tenniel's figures in the background. It's almost like a deliberate, elaborate joke on Thurstan's part.

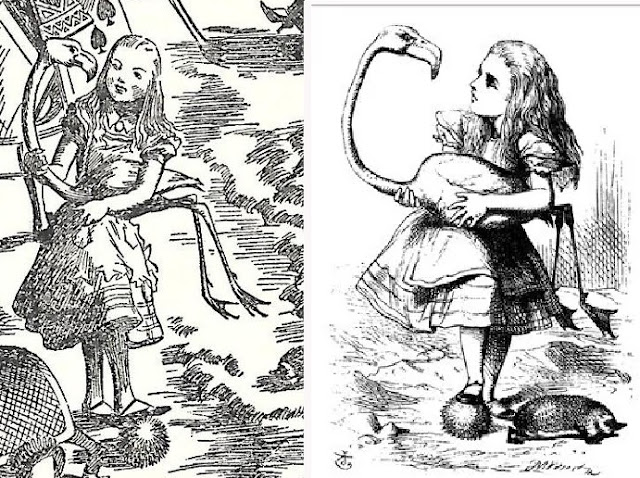

There are Thurstan illustrations where he at least seems to

get away from Tenniel. Let’s have a look at Thurstan’s illustration of the

croquet match

On the surface it seems as if Thurstan has done the same thing here as we’ve seen in other illustrations. The Tenniel scene has been rotated clockwise and we’re looking down from slightly above. However Edgar has significantly moved away from, or beyond the original in a couple of ways. The use of perspective here makes it seem as if Alice is a long way below Humpty even though that wall doesn’t in itself look particularly much taller than Tenniel’s. It’s clever and it foregrounds Humpty, whose haughty appearance in my opinion fits the text a little more than the Tenniel Humpty’s cherubic face. As he did with the Tweedles, Thurstan gives Humpty a more contemporary set of clothes than the costume Tenniel gives him.

Another difference is that while the Tenniel shows vegetation

just peeping over the top of the wall, Thurstan shows a wood in the background.

What makes it even more clever is that the wood is a pretty Tenniel-esque

background feature. My research on Edgar Thurstan yielded disappointingly little

about him, but the one illustration that kept coming up in searches was his

Humpty Dumpty, and I can understand this.

Let’s look at the way that both depicted the huge Alice

squashed in the White Rabbit’s house.

Stylistically these could almost be two different renditions of the same scene by the same illustrator. Shading, with the hatching and cross hatching is so effective in both of these illustrations. In fact, they are not even that different. Both depict Alice with her left arm sticking out of a window with a leaded diamond lattice. In fact the background of both is very similar, although in this case it’s the Tenniel which reveals more than Edgar’s. With Thurstan’s Alice sitting up, it could almost be the Tenniel scene, just a couple of seconds later.

I’d like to look at two pairs next, depicting the Red Queen

from Looking Glass.

It’s easy to look at the depictions of the Red Queen here and the positions of the Alice figures and only really see the differences. Yet there are similarities. Thurstan’s is a mirror image and for once we the viewers are looking almost straight on. Both pairs stand in front of a wood, although the trees are bare in Tenniel’s while Thurstan’s has leaves on the trees and Tenniel-esque roses on the ground. With the figures, there’s clear differences between the two queens. Tenniel’s Red Queen leaves you in no doubt that this is a chess piece, from the pedestal right up to the crown. The crown that she wears is obviously based on the top of a queen in a traditional chess set, but not as much as the crown worn by Thurstan’s queen. Hers is very clearly exactly the same as that on top of the queen in a classic Staunton set. However this is the only way that Thurstan’s queen here resembles a chess piece. Her face is much fuller than the very angular face of the Tenniel queen. In fact if she resembles anyone it is Tenniel’s Queen of Hearts. The sceptre she bears, though, is pretty much the same as that held by Tenniel’s Queen.

I find the position Thurstan has put Alice in, curtseying

to the Queen, to be more effective than Tenniel’s, bringing to mind the Red

Queen’s advice to ‘curtsey while you’re thinking. It saves time.’ – Yes, it’s

the Red Queen who says it, although the Queen of Hearts does in the original

Disney movie. It illustrates a point I’ve made about Tenniel before. His

illustrations are often presented as if they are still tableaux on stage. They

are beautifully observed, but lack movement. Thurstan’s often have just a

little more energy. You can see this in the illustrations of Alice picking up

the Red Queen at the end of the novel.

This time Tenniel’s Queen looks a little less angular and a little fuller of face. This makes her look shorter and more compact just as if she is shrinking back into the chesspiece that she was. This is clever. By comparison Thurstan’s Queen looks less full of figure or face, partly because so much of her is covered by Alice’s hands. Speaking of hands her hands and arms are far more expressive than Tenniel’s. They give a more dynamic feel to the illustration, an impression added to by the detail of the falling sceptre. However, that being said I do feel that the same features that bring movement and energy to Thurstan’s illustration work against it conveying the idea of the Red Queen turning into a chess piece in the way that Tenniel’s does.

Although Thurstan didn’t – or couldn’t – take the opportunity

to depict the two illustrations showing both sides of Alice as she passes

through the Looking Glass, he does echo Tenniel in having before and after

pictures showing the Red Queen before and after turning back into the black

kitten. Like Tenniel, Edgar reproduces his queen’s pose in the pose of the cat.

I have to say that I feel there is more of a kitten about Tenniel’s

illustration, while Thurstan’s seems more of a small cat rather than a kitten.

Let’s look at a couple of illustrations in

which Edgar gets further away from Tenniel. First Alice and the creatures from the

caucus race.

I think that we can say the same about the next pair.

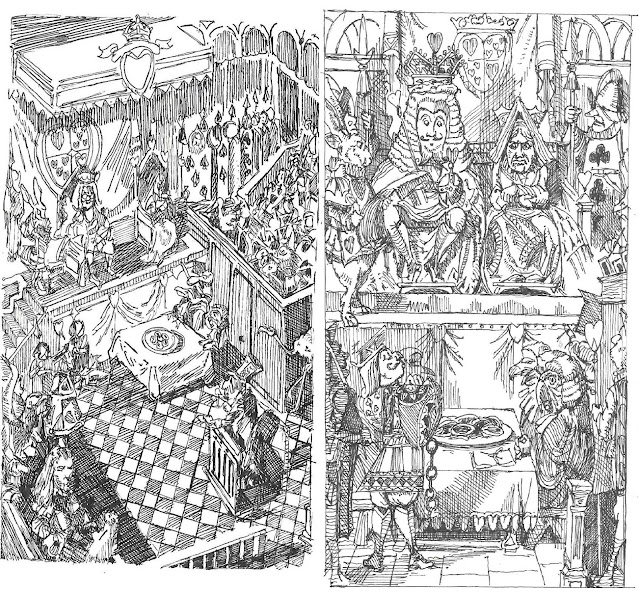

Look at the overview of the court of the King and Queen of

Hearts.

Speaking of chairs, we ought to take a look at Thurstan’s illustration

of the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party.

So we finish with Thurstan’s final illustration from the

Queen Alice chapter of Alice Through The Looking Glass.

-------

Well, that’s the illustrations, just 21 of them, and all of

them seem to owe a greater or lesser amount to Tenniel’s. How about the man,

though? In my attempts to find out any information about Edgar Thurstan I’ve

drawn almost a complete blank. I’ve found references to one or two other books

he illustrated, but that’s it. I have found references to a Captain E.B. Thurstan

in the Australian Army at the end of World War II. If this was our man, then it

might explain why there’s so little information, if his UK career was a very

short one. If I ever get round to inventing a time machine I’d like to seek him

out, and ask him just a few questions, namely

Who decided to draw so heavily on Tenniel’s illustrations,

Odham’s or yourself, and what was he reason behind the decision?

Why only 21 illustrations for the whole of the two books?

What was the thinking behind the scenes you chose/were

instructed to illustrate and those you chose/were instructed not to illustrate?

What were the thought processes behind your choice of the

viewer’s position in relation to the scene?

The caterpillar. What happened, mate?

Maybe it’s not so difficult to see why he is one of the

forgotten Alice illustrators. So many of his illustrations do draw so much on

Tenniel’s, so that there’s little that appears strikingly original. Some of the

more original illustrations are among the less successful in my opinion. Also,

he only made 21 of them. This means that there is no Thurstan illustration of

beloved characters and episodes like Father William, The Walrus and the

Carpenter, the Cheshire Cat, and the Jabberwock. So I can understand why he’s

forgotten. But I think it’s a shame.

It's not that difficult to make a workable copy of the

Tenniel illustrations. I know, I've done all 92 of them. All it really takes is

a good eye and a fairly steady hand. However It takes considerable technical

skill to take a Tenniel illustration and do what Thurstan did with it to

produce something which was never just a straight copy, even in the case of the

most similar illustrations, such as those of the interior of the train

carriage. I haven't tried, but I doubt that I could do it, even taking Thurstan's

methods as a guide.

It's quite possible I would never have been as interested in Thurstan’s illustrations if I hadn’t encountered them at such a early age, but it’s pointless to think that way since I did encounter them then. But I honestly feel that Thurstan should be valued for what he achieved as an Alice illustrator.

No comments:

Post a Comment