It seems like a dream now, looking back on 1982. I’m 60

years old as I write this – back then I was 18. In terms of physical age, forty

two years is a long enough time anyway, but when you consider all that has

happened since it’s much longer. In personal terms in the Autumn of 1982 I’d

only just taken my first ever trip abroad, to Greece. I had yet to win a place

at University, let alone train as a teacher. Now, I’ve just retired from the

job. I didn’t even have a girlfriend at the time – within four years I’d be

married with a child. My Nan had already predicted that one day I would win

Mastermind, but sadly she wouldn’t live to see that prophecy come true a

quarter of a century later. In the wider world there was no internet. Money was

something you carried in your wallet or your pocket and not on a card. Britain’s

fourth TV channel had only begun broadcasting earlier that year. I could go on,

but you get the picture, I’m sure.

Earlier in the year Tower Bridge had reopened its two high

level walkways for the first time in my lifetime. The bridge first opened in

1894 and the two high level walkways between the towers acquired a reputation

as a haunt of pickpockets and ladies of the evening to use a charming old world

phrase. They were closed in 1910.

The walkways were refurbished and reopened in 1982 to house

the Tower Bridge exhibition. Even back then I was in love with London and its history,

so a visit was pretty much a given. Very interesting it was too. The start of

the exhibition concentrated pretty much on Old London Bridge. I found it fascinating.

Years later I discovered Patricia Pierce’s 2002 book on Old London Bridge and I

couldn’t help thinking what a great Mastermind subject it might make. The rest,

as they say . . .

Coming back to 1982, I began to think about how many of

London’s Thames Bridges I’d never crossed. Which was most of them, it turned

out. So the idea came to me to see just how many I could walk across in a day.

This was about 10am. By about 2 pm I reached Putney Bridge – which is only a

bit more than 7 miles away, and had to call it a day.

I never got round to walking across the other bridges to

complete the challenge. However, 2 years later I was in my first year at

University. I’d been cycling everywhere and was probably the fittest I’ve ever

been in my life – not that this is actually saying that much. During the summer

holiday I would cycle from home in West London along the pilgrimage route to

Canterbury all in one day. So when I cycled back across London to my student

hall on the edge of Blackheath at the start of my first summer term it occurred to me

that this would be a good opportunity to cross all of the bridges on the way.

So I did.

I missed out on rail bridges with no footbridge, of course,

and also on bridges which hadn’t actually been built yet – the Millennium Bridge

and the Golden Jubilee Bridge come to mind. These would all be crossed in years

to come. Since then I’ve maintained an interest in London’s Thames Bridges – so

much so that the History of London Bridge would be my Mastermind Grand Final

subject. So in the summer of 2024 I challenged myself to draw all of the

bridges. Here is where I am so far.

1) Hampton Court Bridge – 1933.

This is actually the fourth bridge on the site. It was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, and I have to say that I rather like it. Of its predecessors the first was possibly the most picturesque, a chinoiserie design which seemed to have been inspired by the Willow pattern. This fourth bridge was opened in the 1930s, and was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens. I think he may have used the red bricks where he did in sympathy with the nearby part Tudor, part Georgian Palace. The big clue that this is a 20th century bridge are the wide elliptical arches. Alone of all of the bridges over the Thames in London, only the northern end is actually in Greater London. The southern end is in Surrey and the responsibility for maintaining the Grade II listed structure rests with Surrey County Council.

Like London Bridge, we do not know exactly when the first

wooden bridge at Kingston was built. Fairly reliable written sources say that there

was a wooden bridge standing here in the second half of the 12th

century, but it’s not impossible that there were other bridges on the site going

back into Anglo-Saxon times.

In 1554 when Sir Thomas Wyatt mounted the rebellion named

after him against the rule of Mary Tudor, the inhabitants of London Bridge

refused to allow him to cross into the City of London. Rather gallantly Wyatt refused to burn the bridge down

but marched his men the almost fourteen miles to Kingston. He shouldn’t have

bothered. The citizens of Kingston partly destroyed the bridge to hinder his

progress, and the people failed to rise in support as he marched back towards

London.

Being wooden the bridge was fairly constantly having to be

repaired or partially rebuilt and the severe frost of 1814 would eventually

sound the death knell for the bridge, just as it would for Old London Bridge.

Originally the 1825 Act of Parliament authorising the building of the current

bridge called for a cast iron bridge, but a rise in the cost of iron led to revised

plans for the stone bridge still standing today. It was opened in 1828 and has

been widened several times. Today it is a grade II* listed building.

Kingston Railway Bridge

The bridge carries national railway lines mostly in and out

of London’s Waterloo. That's just about all I have to say about this first railway bridge across the Thames in London, working our way downstream.

Teddington Lock Footbridges

These are two footbridges, situated just upstream of Teddington Lock. There is a small island between the bridges. Possibly the most interesting thing about these bridges is that they are completely different in style and structure.

The two footbridges were built between 1887 and 1889, funded by donations from local residents and businesses. They replaced a ferry which gave its name to Ferry Road at Teddington. The most notable thing about the two bridges is how different they are considering that they were built at the same time as part of the same project. The southern bridge consists of a suspension bridge crossing the weir stream which is the main feature of the sketch and it links the island to Teddington itself. The northern bridge is an iron girder bridge, which you can see part of on the extreme left of the drawing. It crosses the lock cut and links the island to Ham on the Surrey side.

The footbridges are both Grade II listed.

Richmond Bridge – 1777

This rather gorgeous stone bridge to me looks like the quintessence of Georgian elegance. It was built in 1777 to replace a ferry service. In order to repay the investment tolls were charged, which actually lasted until 1859. Talk about long-term pay offs. It was the 8th bridge to be built across the Thames in what is now the Greater London area, but the seven earlier bridges were all demolished, making it the oldest. I used to go ice skating regularly in the old Richmond Ice Rink. I'd take the 65 bus from Ealing Broadway on Sunday afternoon, and walk across the bridge then along the towpath. I think that the ice rink has gone now, but at least the bridge, which is grade 1 listed, remains.

The first Richmond Railway Bridge was built for the London

and South Western Railway in 1848. This made it one of the very first railway

crossings over the Thames. There was fairly heavy use of cast iron in the

structure of the bridge, and the cast iron was largely replaced by steel during

the first decade of the 20th century. This second bridge which

incorporates many elements from the original bridge in its construction was

built between 1906 and 1908 and this is the bridge still standing. In 2008 the

bridge was Grade II listed in order to protect it from unsympathetic future

alterations.

Twickenham Bridge

Here’s a piece of trivia for you. Where was the first Gatso speed camera in the UK installed? Answer – on Twickenham Bridge. The identity of the first driver fined through being caught by the camera? That I don’t know. Thankfully not me.

So, Twickenham Bridge. If you look at it, you’ll see those

wide, elliptical arches which show it’s a child of the 20th century.

A concrete child of the 20th century. 1933 to be precise. OK, now my

view is this. Concrete is a remarkable material. It was extensively used by the

Romans, believe it or not. We can argue about how suitable a material it is in

the damp British climate, but even leaving aside some of the structural problems you

can get with ferro concrete buildings, bare concrete is just plain

ugly to me. Even when you texture the surface it just becomes grubby and

depressing. Lord knows we have enough grey in this world as it is. It’s a

shame, because the lines of Twickenham Bridge are elegant and unfussy. I think

it looks better than the slightly younger Waterloo Bridge and the current

London Bridge as comparisons. But just downstream is the Richmond Lock and

footbridge, and I’m sorry, but it shows just how lacking in character

Twickenham Bridge is by comparison. Nonetheless, the bridge is Grade II*

listed.

Richmond Lock and Footbridge

This one I have crossed twice, and walked past many other

times, and until the first time I crossed it this always struck me as a bit of

an unusual thing. It seemed to me that it was only going halfway across the

river, until I actually crossed it and saw all the lock gubbins.

This one I have crossed twice, and walked past many other

times, and until the first time I crossed it this always struck me as a bit of

an unusual thing. It seemed to me that it was only going halfway across the

river, until I actually crossed it and saw all the lock gubbins.So, what else can we say about it? Well, it’s a grade II*

structure and is the only lock that’s owed and operated by the PLA – Port of

London Authority. It was built to keep parts of the river navigable, and was

opened in 1894.

I have to say that this does have a bit of late Victorian

style about it. They didn’t do things by halves did the late Victorians and

Edwardians. Shrinking violets they were not and this building has bags of confidence.

One interesting thing to see on the footbridges are the old tollbooths. They

were still charging pedestrians at the start of the second world war.

Kew Bridge

Walking between the Richmond lock footbridges and Kew

Bridge is very pleasant on a nice day, since you have the Royal Botanical Gardens

to the Kew side on the south, and Syon Park on the Brentford side on the north.

There’s been a bridge over the Thames at Kew since 1759. It

was dedicated to George, Prince of Wales, who a year later became George III. His

predecessor, his grandfather George II had leased a grand house in Kew for his

daughters and over time a whole palace complex – Kew Palace – grew there. Poor

old George III was virtually kept a prisoner at Kew during his first bout of ‘madness’

in 1789. At about the same time the first bridge, made of wood and stone, was

replaced by the second, built alongside it. This one, to be fair, lasted more

than 100 years, but not long after its centenary it was felt that it was too

narrow and could not cope with the volume of traffic, and so it was demolished,

with a temporary wooden bridge put in its place while the current bridge was

built.

There’s a fair chance that I’ve crossed Kew Bridge more

times than any other across the Thames – only Richmond Bridge might beat it. I

used to go ice skating every Sunday in Richmond, and the route of the number 65

bus from Ealing crossed the river at Kew.

Kew Railway Bridge

Well, fair play, the bridge has been standing here since

1869 and it’s still going strong. It was built for the LSWR – London South

Western Railway, and today it is shared by the London Overground and the London

Underground. So working downstream this is the first bridge we’ve encountered

which carries the Tube. That’s another thing that endears it to me.

It is grade II listed. I know that this sort of structure

is not to everyone’s taste, but I like the honesty of a bridge that has all of

its workings on show. Think about it. Would the Forth Bridge, or the Eiffel

Tower (a structure that in itself owes a great deal to railway architecture and

engineering) look better if all of the girders were covered up away from sight?

I rest my case.

Chiswick Bridge

This is the last bridge the crews from Oxford and Cambridge pass beneath in the annual University Boat Race. At first glance you might not notice that the main building material is concrete, like Twickenham Bridge, because most of it is faced with Portland Stone. Good choice. However the five wide elliptical arches of which only the three central ones span the river are the giveaway that this is another 20th century bridge.

Chiswick Bridge, Twickenham Bridge and the rebuilt Hampton

Court Bridge were all opened on the same day in 1933. Improvements in transport infrastructure during the end of the 19th century and the beginning

of the 20th had made commuting more attractive. Up to the end of the

Victorian period, Hammersmith had been on the outskirts of London. A rapid

growth of the population to the west put pressure on the existing bridges

upstream of Hammersmith which necessitated the building of these. My own family

first moved to Ealing, my home borough, at this time with my mother’s parents and

grandparents moving there in 1907, and my father’s parents settling there just

after the outbreak of World War II.

Coming back to the Boat Race, there’s an unobtrusive stone

marker to show where the race ends just upstream of the bridge.

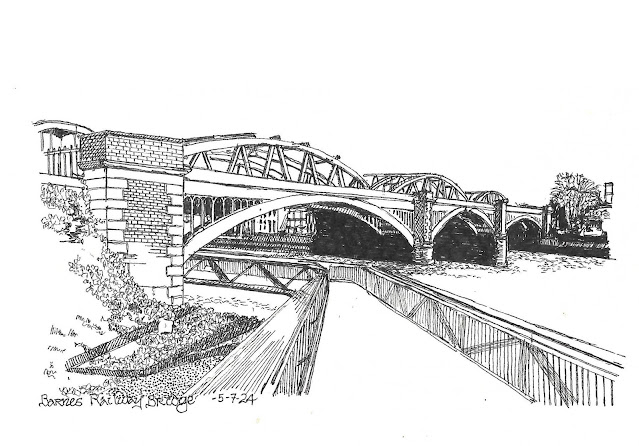

Barnes Railway Bridge

I’ll be honest, Chiswick Bridge has never really blown me

away. But I really like Barnes Railway Bridge. Working downstream it’s the

first bridge we’ve come to that combines a railway and a footbridge. The only two

others are the combined Hungerford and Golden Jubilee Bridges and Fulham

Railway Bridge, which we’ll come to fairly soon. It’s somehow very close to my

platonic ideal of what a railway bridge should look like.

The first Barnes Railway Bridge was built in 1849. Like Richmond Railway Bridge upstream it performed pretty admirably, but came under question for the use of cast iron in its construction. I believe that a cast iron bridge in Norwood collapsed suddenly in 1891. So the LSWR built this successor which opened in 1895. Wrought iron is used extensively in the structure, which was able to incorporate parts of the original bridge, and I think it has a little bit of a ‘belt and braces’ appearance, with the metal arches holding the carriageway, and the girdered arches supporting it from above. I like it.

Hammersmith Bridge

The current Hammersmith Bridge was designed by the great Sir Joseph Bazalgette and erected in the 1880s. This isn't maybe the place or time to go into exactly what made Sir Joseph a great unsung hero of the story of London, but if you're interested he is well worth a google. The previous bridge on the site was the first suspension bridge across the Thames. It was designed by William Tierney Clark and opened in 1827. The bridge was very similar to William Tierney Clark’s own 1837 Chain Bridge across the Danube in Budapest – which is still standing and I enjoyed walking across in 2017.

Tierney Clark couldn’t have envisaged how

the volume of traffic that the bridge would carry would exponentially increase

over the next few decades. The authorities at the time were appalled at the

possibility of the bridge collapsing when the annual crowd of over twelve

thousand people gathered on the bridge to watch the University Boat Race and they would rush from one side to the other as the Oxford and Cambridge boats passed

beneath. It’s always struck me as ironic just how important the boat race was

to people of Hammersmith and West London as a whole, and how whole families would

be passionate supporters of one of the two universities. Despite the fact that

there was sod all chance of any of these families’ kids ever getting to either

seat of learning, this kind of partisanship was still very common when my

parents were kids in the forties and fifties.

Coming back to the bridge, it was during

the 1860s when my ancestor John Olive was walking across the bridge to work

that he had a fatal heart attack. Even more macabrely his son, James, would have

a fatal heart attack while walking 20 years later – this happened on the South

Ealing Road. Both had inquests carried out in the venerable Dove Public House

in Hammersmith.

Putney Bridge

If you’re of a similar age to myself maybe the same thing happens to you every time you hear the name Putney. When I hear it in my mind’s ear I immediately hear Rowan Atkinson’s Lord Edmund Blackadder.

Edmund: Tell me young crone. Is this

Putney?

Young Crone: That it be

Edmund: Yes it is, not that it be.

I’m not a tourist.”

No? Well, I guess that you had to be there.

Little things, as they do say. Right then, it’s pretty well

known that there’s been a London Bridge since Roman times. The first stone

built London Bridge was completed in 1209. How long do you think it took before

the next bridge across the Thames in the area we think of now as London was

built? I’ll tell you. 520 years! There was not another bridge built until 1729.

And that bridge, dear reader, was Putney Bridge. Basically the City of London

blocked the building of any other bridges to protect the interests of the

watermen, who worked the ferries across the Thames.

The 1729 bridge I hasten to add, was not the Putney Bridge

we know and love today. The story goes that Britain’s first Prime Minister, Sir

Robert Walpole, following an audience with the King, reached Putney and was

unable to drag any of the ferrymen out of the pub to row him across the river.

He returned to Westminster via another route in high dudgeon and the experience

seems to have motivated him to get a bridge between Fulham and Putney built. This

was a wooden bridge, a rather fetching one judging by contemporary engravings.

The bridge had a pretty decent long working life too, but the writing was on

the wall for it from 1870 when it was damaged when a barge collided with it.

The current stone bridge was opened in 1886. Like

Hammersmith Bridge it was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette, although it is

very different in style from that bridge. This one is a lot more conservative – with

more of an understated elegance.

On a personal note, when I came up with the idea of walking

across all of the bridges back when I visited the Tower Bridge exhibition in

1982, Putney Bridge was as far as I got.

Fulham Railway Bridge

Ladies and gentlemen, let me introduce you to the bridge with no name. Yes, we call it the Fulham Railway Bridge, but it has also been known as Putney Railway Bridge, and even The Iron Bridge. You can call it what you like since it doesn’t have any official name. For me, I’ll keep calling it Fulham Railway Bridge.

So, what have we got? Well, it’s a relatively unassuming

lattice girder bridge built for the LSWR in 1889. You know from my comments

about Kew Railway Bridge that I have something of a fondness for the

unashamedly industrial appearance of this kind of railway bridge. Nowadays it

carries the London Underground District line branch to Wimbledon.

Wandsworth Bridge

Well, what can we say about what is, to my mind, one of the least distinctive bridges to cross the Thames in Greater London? This is the second bridge on the site. The first was built in 1873, during one of the busier periods of bridge building in London. The expectation was that the Hammersmith and City Railway was going to build a terminal on the north bank of the Thames here. They didn’t, and this was one factor that contributed to the first bridge’s relative failure. There were others. The bridge was a lattice girder bridge and it looked a little like a railway bridge. Problems with the approach roads and with weight and speed restrictions on the bridge all meant that it never made enough money from tolls even to keep up with the costs of maintenance.

The bridge couldn’t carry trams or buses and replacing it

was first mooted in the 1920s. Replacing Putney Bridge was deemed more urgent,

and so it wasn’t until 1935 that the Ministry of Transport agreed to the replacement.

Demolition of the old bridge began in 1937, meaning it lasted a little more

than 60 years.

The current bridge is a cantilever steel bridge that

crosses the river in three spans. The outbreak of World War II caused a

shortage of steel and meant that the bridge could not be completed and opened

until September of 1940. I want to be kind about the bridge, or at the very

least, I don’t want to be mean about it. It isn’t ugly – it’s a bit too nondescript

to be ugly. But, and I want to stress this, it does the job which is all the

more praiseworthy considering that it is one of the busiest bridges in London,

carrying an estimated 50,000 vehicles a day.

Battersea Railway Bridge

It’s easy to dismiss Battersea Railway Bridge as just another railway bridge across the Thames. However, it’s really not without an interesting history.

For one thing, it’s not just one of the oldest railway

bridges across the river, it’s one of the oldest bridges across the river full

stop. Yes, a fair number of bridges were built across the Thames before this

one was built in 1863, but most of them have long since been replaced. This is

still substantially the same bridge. Today the bridge carries the West London

line of the London Overground. Originally it linked railways in South London

with the termini at Paddington and Euston. The link with Paddington meant that

the bridge originally carried broad gauge lines as well as standard gauge.

Trust me, that’s a big thing to a railway buff.

While we’re on the subject of railways, the bridge was used

exclusively for freight throughout the 19th century and the first

passenger train didn’t cross it until 1904. The structure carries the railway

across five wrought iron arches and is grade II* listed.

Battersea Bridge

Battersea was where my Scottish Clark Grandfather Thomas married my Nan Dorothy and it’s also where my father George was born. He was very little when Tom and Dorothy moved the family to Acton. As far as I know that had nothing to do with Battersea Bridge, mind you.

The current bridge is the second Battersea Bridge. The

first was opened in 1771 and came to prove a popular subject with artists, despite

the fact that it really wasn’t terribly good. It was planned as a stone bridge

but there were problems with raising the investment to build it so a wooden

bridge was built. If you look at paintings of the bridge, or old photographs it

was certainly an eye catching structure. It had 19 spans and must surely have

posed a challenge to river traffic. Old London Bridge itself had 19 spans, and

this had the effect of creating a weir effect at certain times, so much so that

at different times of the day passing downstream could be like shooting the

rapids. For all that the bridge was not demolished until 1885.

So, the current Battersea Bridge was designed by our old

hero, Sir Joseph Bazalgette. From a distance it doesn’t necessarily look that

much to write home about. That’s possibly partly due to the predominantly dark

green colour scheme, I would think. When you get closer though there’s enough

decoration while the five cast iron arches give a feeling of strength and

permanence.

Coming back to paintings of the old bridge, old Battersea Bridge was featured in Whistler’s “Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket’. The critic and know-all John Ruskin in his review accused him of ‘flinging a pot of paint in he public’s face.” Whistler sued, and was awarded damages of one farthing, which virtually ruined him.

Albert Bridge

I’m from Ealing in West London and I attended the University of London Goldsmiths College. Goldies is in New Cross in South East London and my student hall, where I stayed for three years, was situated in Lewisham, right on the edge of Blackheath. I didn’t used to come home every weekend, but I did do so fairly often. Now, if you know London you’ll know that it’s a place where travelling relatively short distances can take a long time. It’s just over 15 miles from Goldies to my old home and I googled it this morning. It informed me that the average duration of a car journey between the two at off peak times is just under an hour and a quarter. Using public transport it’s a little more than an hour and a quarter. I would cycle between the two and as I became fitter, I became a lot quicker, to the point where I could do the journey in a little less than forty minutes. My preferred route involved riding along the Chelsea Embankment just a little downstream of Battersea Bridge, past the Albert and Chelsea Bridges eventually crossing over Vauxhall Bridge. So it makes me happy that I’ve sketched this far now.

Of the bridges I’ve just mentioned I think that the Albert

Bridge is the prettiest. I did think always think that the Albert Bridge was

designed by Joseph Bazalgette, but no. It was actually designed by Rowland

Mason Ordish in 1873. It’s an interesting design too. At first glance it looks

like another suspension bridge, but it wasn’t. It was built according to the

Ordish-Lefeuvre system, as a cable stayed bridge. Look, I’m not an expert on these

things, but I do know that the design proved to be a bit unstable and this is

where the Bazalgette connection comes in. It was Bazalgette who incorporated

elements of suspension bridge design into it.

You can argue that the success this brought was limited.

The bridge develop a reputation for instability, and like the first Wandsworth bridge

it never reaped enough revenue from tolls to pay for maintenance and up keep of

the bridge. Speaking of toll booths, these still exist on the bridge, in fact I’ve

painted one of them once. They have signs warning troops to break step when

crossing it.

One of the things that might strike you when you cross the

bridge is how narrow the roadway is. So in practical terms, this is not a great

success as a bridge, and although it is still open to traffic there are very

strict restrictions on its use and it is one of London’s least used bridges.

However on a clear evening, when it’s all lit up with LEDs, it’s undeniably

very, very pretty.

Chelsea Bridge

Here’s a question for you. Why was the Albert Bridge named after Prince Albert? Well, just downstream was the original Chelsea Bridge and this one was officially called the Victoria Bridge. There you go.

The purpose of the Victoria Bridge/ Chelsea Bridge 1 was to

facilitate the development of the new Battersea Park area. It was originally

planned in the 1840s. However the work on the Chelsea Embankment caused over a

decade of delays and the bridge was not actually opened until 1858. Photographs

of this first Chelsea Bridge show it as a relatively stately looking suspension

bridge, just a little reminiscent of the current Hammersmith Bridge,

Like a significant number of 18th and 19th

century Thames Bridges this was a toll bridge – which was a bit of a cheek

considering that it was built with public money. Like the majority of those

toll bridges, it was not a commercial success. Which goes to prove the old adage

– if you build it they will come, but they won’t pay to cross over it -. Tolls

were finally abolished in 1879. There’s an interesting story as to why the

bridge was renamed Chelsea Bridge. Basically the structure of the bridge was

unsound and the authorities didn’t want the bridge being associated with the Queen

in case it collapsed.

Even if it had been sound by the 1920s it was obvious that

it could not cope with the amount of traffic wanting to use it which was only

likely to increase. The bridge was finally demolished and replaced by the

current bridge which opened in 1937. The current structure was apparently the

first self-anchored suspension bridge in Britain – which I’m told means that it

is anchored to its own deck rather than to the ground. Fills one with

confidence.

It has always struck me as something of a plain jane of a

bridge. It’s clean and unfussy but lacks adornment when compared with the other

bridges on this section of the river. I don’t know if this is what was meant,

but the pillars carrying the cables above the deck have always looked a bit

like Egyptian obelisks to me.

Grosvenor Railway Bridge

I don’t know why but I always thought that this bridge was called the Victoria Railway Bridge. Maybe it’s because it carries rail traffic into Victoria station. The bridge was first built by Sir John Fowler, and in an era of great British engineers his was a name to conjure with. His lasting monuments, if you need any, are the Metropolitan Railway which was the very first underground railway in the world, and the Forth Bridge which he co-designed. Mind you, he did have a few failures along the way. Using steam locomotives in underground railway tunnels is not ideal because of the amount of smoke that they produce, so Fowler came up with a design for a ‘smokeless’ engine, nicknamed Fowler’s Ghost, Basically it relied on heat retaining bricks in the boiler to maintain the temperature and ensure a steady supply of steam. Its main drawback was that it didn’t work.

Still, the Grosvenor Railway Bridge was the first to be

built in central London and here Sir John was on much firmer ground should you

pardon the metaphor. His bridge originally carried just 2 tracks across five

arches. Five years later it was widened to add a further four tracks which

would accommodate increased traffic from the London, Brighton and South Coast

Railway and the London, Chatham and Dover Railway. In 1907 the bridge was

widened again to accommodate a further track for the LB&SCR.

Between 1967 and 1968 the bridge was completely renovated

and modernised, and little remains of the materials Fowler originally used apart

from the cores of the original piers. Within a year of the completion of this

work Grosvenor Bridge was claimed to be the world’s busiest railway bridge,

carrying in excess of 1000 trains each day.

Today it’s a perfectly pleasant, unfussy railway bridge,

even if it does lack a little impact.

Vauxhall Bridge

This is the second Vauxhall Bridge. The first had a

complicated genesis. The purpose of the bridge was to open the South Bank of

the Thames for development. There was opposition to the building of any bridge

here from the proprietors of the original Battersea Bridge. In the end the

Vauxhall Bridge Company was obliged to compensate them for any loss of revenue.

The original design was rejected. Then the great John Rennie – don’t worry, we’ll

get to him later – had a design accepted, but the developers ran out of money

to build it. So Rennie submitted a cheaper design. This was rejected. Samuel Bentham

submitted a design. Construction began but it wasn’t long before concern was

expressed about the construction of the piers, and a report by engineer James

Walker led to the design being abandoned. So Walker was appointed to design and

build a bridge of 9 cast iron arches with stone piers, which would be the first

cast iron bridge over the Thames. So, finally the bridge opened in 1816. It was

named the Regent Bridge after the future George IV, but pretty soon afterwards

was renamed Vauxhall Bridge.

The developers believed that the areas either side of the

bridge would become well to do suburbs, so they set high tolls at the start.

Instead the area became home to poor factory workers in the Doulton factory,

and also to the Millbank Penitentiary. Despite this though revenue did improve

from the tolls, until the Metropolitan Board of Works (the Government

department at the time responsible for public infrastructure works) had an Act

of Parliament passed enabling it to buy all of the bridges across the Thames from

Hammersmith Bridge to Waterloo Bridge and abolish the tolls. Vauxhall Bridge

was bought in 1879 and tolls were lifted. Not long after this, though, a report

into the bridge established it was in poor condition and in 1895 an Act of Parliament

was passed allowing the bridge to be replaced.

The original design for the new bridge by London County

Council chief engineer Sir Alexander Binnie was for a steel bridge. Asked to

think again he came up with a five span concrete bridge to be faced with

granite. After the piers had been built it was discovered that the clay of the

riverbed could not support the weight of a concrete bridge, and so the long

suffering Binnie and civil engineer Maurice Fitzmaurice designed a steel

superstructure to fit the piers. During the construction many influential

people commented with dismay about the very functional design and so sculptors

Frederick Pomeroy Alfred Drury were commissioned to make large,

personificational statues which would eventually be attached to the sides of

the bridge. Upstream there are Pomeroy’s Agriculture, Architecture, Engineering

and Pottery, while Drury’s Science, Fine Arts, Local Government and Education

adorn the downstream side.

Vauxhall Bridge was the first bridge to carry trams across

the river. Sadly the tracks were ripped up when trams ceased operating in

London in 1951. There’s been a lot of development in the last 40 years

particularly on the south bank here, and in 2008 the bridge was give a grade

II* listing.

Lambeth Bridge

Red is used prominently in the colour scheme of Lambeth Bridge. Why do you think that should be? Well it’s all to do with the Houses of Parliament, which lie on the north bank of the Thames between Lambeth Bridge and Westminster Bridge. To the west, on the Lambeth Bridge end is the House of Lords, and the benches within the Lords chamber are red. At the east end, the Westminster Bridge end, is the House of Commons, with its green benches. Which is why green is the main colour of Westminster Bridge.

Back to Lambeth Bridge, then. On the north bank there’s a

road called Horseferry Road on the approach to Lambeth Bridge, which shows that

this was originally the site of a horse drawn ferry. Remember, there was no

other bridge than London Bridge in central London until the 18th

century. The first Lambeth Bridge wasn’t opened until 1862, and it was a plain

and austere suspension bridge. Yes, it was a toll bridge and no, the tolls didn’t

raise the expected revenue. This is a story we’ve heard before. The LCC bought

it in 1879 and abolished the tolls. The Metropolitan Board of Works found that

the bridge – less than two decades old at this point – was badly corroded, and

vehicles were banned from it in 1910.

Parliamentary approval for a replacement road bridge was

granted in the 1920s, but a flood in the area before work had begun delayed the

building of the bridge. Finally the current five span steel arch bridge opened

in 1932.

Westminster Bridge

A bridge at Westminster was first proposed during the Restoration

period, but the opposition of the Corporation of London and the waterman’s

lobby proved a tough obstacle to shift. It wasn’t until after London’s second

bridge was built at Putney that Parliament approved the building of a bridge at

Westminster, and even then it took 11 years to build, finally opening in 1750. Wordsworth

wrote his poem about the bridge in 1802, but even then it was probably

suffering from the design flaws that would see it suffering from incurable

subsidence by the time it reached its centenary. Like London Bridge the original

Westminster Bridge consisted of many narrow arches, and the narrowness of the

arches contributed to the current scouring the river bed away which led to the

subsidence.

The bridge was then demolished and the current Westminster

Bridge was built to replace it. It was opened in 1862. The bridge has 7 cast

iron arches, and much of the ornamentation was designed by Charles Barry, who was the architect of the Palace of Westminster which was in the middle of the

long process of being built at the time. The current Westminster Bridge might

not be the most beautiful on the river, although it’s perfectly inoffensive.

However, it has to be said that if you’re standing on the Southern end of the

bridge the view to the northern end, taking in the Palace of Westminster and in

particular the Elizabeth Tower – commonly known as Big Ben – is one of the finest

on any bridge across the Thames.

Trying to be a little less damning of the original bridge,

it did at least have the effect of opening the door to the development of more

bridges in London. Prior to the building of Westminster bridge, only 1 new

bridge, Putney, had been built in the previous 500 years. In less than 30 years

four more had been built.

Currently, Westminster Bridge is the oldest road bridge

across the Thames in central London, albeit that Richmond Bridge is many

decades older.

Hungerford Bridge and Golden Jubilee Bridges

Do you count these as one bridge or as separate bridges? Well, they are listed as separate structures, even though the two Golden Jubilee footbridges share the same piers as the Hungerford Railway Bridge. I’m depicting them as one for a simpler reason than that. It’s very difficult to do a picture of one without the others. So I’m not.

Right, here’s a question for you. If you asked this question - can you name a Victorian Engineer? - whose would be the name that came

up more than any other? Chances are it would be Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Brunel

was the chief supervising engineer of the Thames Tunnel from Wapping to

Rotherhithe that had been designed by his father Marc Brunel. He didn’t design

or build any of the existing bridges across the Thames in London, however he did

design and build the original Hungerford Bridge.

This was a suspension bridge opened in 1845 carrying railway lines across the river from the then Hungerford market to what would become the Waterloo area. In 1859 the bridge was bought by the South Eastern Railway, to extend the line into the new Charing Cross station. The decision was made to replace the bridge. It’s a bit of a shame since Brunel’s bridge was actually rather picturesque. Contemporary pictures show that a pair of rather fetching Italianate red brick towers supported the central span. These were demolished but the new bridge did use the buttresses of Brunel’s bridge. You might well have seen or even passed over a bridge held up by the chains from Brunel’s Hungerford Bridge since these were reused in Brunel’s Clifton suspension bridge in Bristol. (Yes, I know that the Clifton Bridge was finished by William Barlow and Sir John Hawkshaw who made some pretty substantial revisions to Brunel's design. I'm impressed if you did.)

The new bridge, which is the current bridge, was a nine-span

wrought iron steel truss bridge, made of lattice girders. You have to look

quite closely to see the details from some angles, mind you, and I do find my attention is drawn away by the white pylons of the two Golden Jubilee bridges and the cables supporting the walkways. The bridge was

originally built with walkways on either side, but the western one was removed

when the railway bridge was widened. In 1996 a competition was held to design

new footbridges either side of the railway bridge, since the lone walkway had

become dilapidated and was felt to be too narrow.

Not claims you could make about the new bridges which are both four metres wide. I have to say that the large white slanting pylons from

which the deck is suspended seem to enter into a rather unsettling dialogue

with the Victorian appearance of the railway bridge sandwiched between them,

but on a sunny day I find the bridges very pleasant to walk across. As for the

name, well with them opening in 2002, the year of Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden

Jubilee, it’s a bit of a no-brainer.

Waterloo Bridge

Trivia question – which bridge across the Thames has a Hollywood movie named after it? Waterloo Bridge, and it had two films named after it, the original 1930 film, and the 1940 remake, which starred Vivien Leigh, who’d only just received her first Oscar for Gone With the Wind. Which is pretty appropriate considering that the original bridge was gone with the wind by this time, while it would be two years before the new bridge opened partially, and five years until it opened completely.

Let’s talk about the old bridge for a while, though. My

favourite bridge ever to cross the Thames is Old London Bridge. We’ll come to my

favourite existing bridge in the fullness of time. Still, I do also have a soft

spot for old Waterloo Bridge. This was originally designed by the Scottish engineer

John Rennie as the Strand Bridge, for the obvious reason it could be accessed

from The Strand. Before it was complete the Battle of Waterloo had been fought

and won and the bridge was renamed Waterloo Bridge. John Rennie would go on to

design the new London Bridge which would be opened in 1831, and there were

certainly similarities in the design of the two bridges. Like people, some

bridges are naturally more photogenic than others, or should I say, more picturesque.

Waterloo Bridge scored highly on this scale. Constable painted its opening, and

Claude Monet painted it no fewer than 41times.

The same scour from the river flow which had earlier done

for the first Westminster Bridge was found to be damaging the foundations of

Waterloo bridge by the mid-1880s. Urgent remedial work had to be carried out

during the 1920s, but this was only ever a temporary solution and in the 1930s

the London County Council made the decision to demolish it and replace it,

despite some opposition from early proponents of architectural conservation.

Right, what links both Waterloo Bridge and the traditional

British red telephone box? Yes, both were designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott.

Scott freely admitted that he was an architect and not an engineer, which is

perhaps why you get to see so little of the actual engineering of the bridge

from the outside. Look, I’ve put on record that I don’t like looking at large

amounts of concrete on the exterior of a structure. However the first time I really

looked at Waterloo Bridge I was impressed by how modern it looked. To me at that

time in the mid 70s it looked every bit as modern as the recently opened London

Bridge. Well, you live and learn, I suppose. For some time after it was opened it was known as the Ladies’ Bridge because of the large numbers of women who

worked on its construction during the Second World War.

Since World War II Waterloo Bridge has had a fairly

uneventful history, with the exception of the Georgy Markov incident. Georgy

Markov was a Bulgarian dissident who worked for the BBC world service, and a

vocal critic of the Soviet bloc. In 1978 he walked across Waterloo Bridge, and

when he had crossed it he was injected with a poisoned micro pellet, probably

by the tip of an umbrella. He died four days later.

Coming back to the original bridge when it was demolished blocks of granite from it were sent to Commonwealth countries across the world. The silver grey beech piles were also cut up and used to make thousands of boxes, many of which were sold during the Festival of Britain. I have several of these boxes in my own small collection.

|

| Old Waterloo Bridge - I couldn't resist doing this one as well |

Blackfriars Bridge

You know, if you take the time to think a little about the

names of various places you can learn a bit about their history. If we take a

very simple one to start with, the name Hammersmith might lead you to think

that it was originally a district where blacksmiths made tools. You’d be right

to think so, although by the time my 3x great grandparents were living there it

was nicknamed Laundry Island. I digress. So the area of Blackfriars derives

from a Dominican Priory built there in the 1270s. The Dominican order of monks

were nicknamed the Black Friars from the black robes they wore. This compares

with the Grey Friars – the Franciscans and the White Friars - the Carmelites.

The Black Friars were pretty much the Stormtroopers of the medieval Catholic

Church.

The priory had gone a long time before the first

Blackfriars Bridge was built. Yes, Blackfriars was one of the bridges built in

the couple of decades following the original Westminster Bridge. Begun in 1760

it was opened 9 years later. This was a bridge of 9 arches made of Portland

stone. Judging by paintings and engravings of the first bridge it was a rather

attractive Italianate structure. Officially it was named the William Pitt

Bridge after the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Elder, whose reputation was

at its zenith in 1760 following the successful conclusion of the Seven Years

War, but it was the informal name based on the district on the North bank that

was served by the bridge that caught hold.

What happened to the bridge afterwards is a fairly familiar

story. While the bridge may have looked elegant and classy, it’s construction

was not made to stand the test of time. Any bridge built in the 18th

century faced a number of challenges. Britain was in the middle of the period

known as the ‘little ice age’ during which the winters were more severe than

they are now. During the life of the first Blackfriars Bridge the Thames froze

over so badly in 1789 and 1814 that Frost Fairs were recorded as being held on the Thames. The 1814 frost,

and the disastrous effects of its thawing sounded the death knell for Old

London Bridge. Immediately following the opening of John Rennie’s London Bridge,

old London Bridge with its 19 narrow arches was demolished. This had the effect

of removing a huge obstacle to the river, which increased its flow and the

scouring effect of the current on bridge foundations. This effect was noticeable

on Blackfriars’ Bridge where extensive repair work was necessary from 1833 for

the rest of the decade. The bridge was finally demolished in 1860.

Building of the replacement bridge was hampered when the

company that won the contract had issues finding stable foundations, which led

to financial issues which bankrupted their main supplier. It wasn’t until 1869

that the current five span wrought iron arched bridge was opened by Queen

Victoria.

Blackfriars Bridge took on a certain amount of notoriety when the body of Italian banker Roberto Calvi was found hanging from one of its arches in 1982. Rumours and unconfirmed stories have since surfaced suggesting that Calvi was murdered by the Italian Mafia, to whom he allegedly owed a lot of money. An Italian court case in 2007 failed to convict men who were accused of carrying out the murder due to lack of evidence.

Blackfriars Railway Bridge

It’s difficult to think of many Thames bridges in London that have been demolished during my lifetime. There’s the granddaddy of them all, Rennie’s London Bridge. Other than that though there’s only Blackfriars Railway Bridge, which was removed and demolished in 1985.

This gets a little complicated. Because, you see, there

were actually two Blackfriars Railway Bridges, one of which, the one in the

picture, remains. The older of the two was the one which was demolished. It was

opened in 1864 by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway. When the bridge was

demolished the huge abutments on either side were preserved in place and these

bear the arms of the company, They’re something to look out for any time you go

to see the Thames bridges for yourself. After the company was subsumed into the

Southern Railway in the 1920s, cross channel traffic was allocated to other

routes. By the time of demolition the bridge was just too weak to bear the

weight of modern trains. The columns that carried the bridge were left in place

and can still be seen alongside the second Blackfriars Railway Bridge.

The second bridge opened in 1886 and was originally called

the St. Paul’s railway bridge. This too was built for the London, Chatham and

Dover Railway. It was designed by William Mills of the railway company, John

Wolfe Barry who would later design Tower Bridge and Henry Marc Brunel (Isambard’s

nipper). It was made with five arches constructed from wrought iron. The

original design called for four tracks but this was increased to seven. The

bridge served St. Paul’s station. This was renamed Blackfriars which became the

name of the bridge from then onwards.

Following the demolition of the other Blackfriars Railway

Bridge, the columns were partially used to support the extension of the

platforms of Blackfriars Station across the bridge. The roofs of the platforms

were installed with solar panels. It makes Blackfriars Railway Bridge the only ‘solar

bridge’ in the UK, and the longest of only three in the whole world.

Millennium Bridge

At the time of writing we’re a year short of a quarter of a century passing since the turn of the Millennium, and it seems strange to think of how big a deal it seemed at the time. Remember the fears over the Y2K bug? Well, whether you’re old enough to remember or not, anything that came about in or around the year 2000 was always going to be doomed to bear the word Millennium somewhere in its name.

The competition to design the new footbridge took place in

1996. The winning design from Arup Group, Foster and partners and Sir Anthony

Caro took its inspiration from a blade of light. And what an innovative design

it is. When you look at the bridge you may be surprised to learn that it is a

suspension bridge. A suspension bridge? But where are the cables? Ah, that’s

one of the clever things. They are below the deck which means that the view

from the deck itself is brilliantly unobstructed. Although possibly the finest view

is looking across the bridge itself from the southern end, where the majestic

bulk of St. Paul’s Cathedral in all its glory seems to beckon you forward. All of

which makes the Millennium Bridge a structure which looks far better to my mind

from on the deck of the bridge, than from the river, where I find that the

blocky concrete supports are a little clunky looking, and the thin metal

profile of the deck just a little underwhelming.

Okay, let’s get the W word on the table. That word is

wobble. The Millennium Bridge was opened on 10h June 2000 and on that day many

people walking across the bridge reported that they could feel it wobbling. I

don’t want to get too technical (because I can’t) but basically suspension

bridges, far from being absolutely rigid, have a capacity to sway slightly. The

Millenium Bridge originally had a tendency to slightly sway from side to side,

as opposed to a traditional suspension bridge having a tendency to move up and

down slightly. The sway caused people unconsciously to start walking in time to

the bridge’s swaying which had the effect of increasing the sway. This is

related to, although not the same as the vertical sway that caused the Tacoma

Narrows bridge to shake itself to pieces in a very famous piece of film.

The engineers at Arup solved the issue through the fitting

of fluid dampers, which I guess are like shock absorbers to the bridge, and in

more than two decades since there haven’t been any reports of any issues with

wobble. I’ve walked across it myself many times, and although I was more than

up for a bit of a wobble I didn’t feel anything. Still, give a dog a bad name.

It’s still not unusual to hear it referred to as the Wobbly Bridge.

Southwark Bridge

Southwark takes its name from the Anglo Saxon Suthringana weorc – literally the fortification (work) of the Men of the South (Surrey). Southwark is the oldest part of South London, developing around the southern end of London Bridge, itself dating back to c.50 AD, soon after the Roman conquest.

It wasn’t until 1811 that Parliament passed the bill for

the building of the first Southwark Bridge, and work didn’t start until 1813.

The bridge was designed by John Rennie who also had Waterloo Bridge on the go

at the same time and would design the replacement for Old London Bridge. This

first Southwark Bridge had three cast iron spans supported by granite piers. In

Charles Dickens’ “Little Dorrit” there are several references to the Iron Bridge

across the river and I had to do a little bit of research to find out that this

was a reference to the original Southwark Bridge. The main purpose of the

bridge was to relieve traffic upon Old London Bridge. Contemporary reports

showed that it was pretty unsuccessful at attracting traffic away from Old

London Bridge. There were a number of reasons why. Firstly there were tolls. Who

was going to pay to use Southwark Bridge when Blackfriars and old London Bridge

were free? Then the bridge itself was pretty narrow. The approach roads were

steep and on the Southwark side very poorly made up.

Predictably enough the bridge company went bankrupt and the

bridge was acquired by the Bridge House Estates which operated a number of bridges

including London Bridge – we’ll talk more about Bridge House Estates when we

get to London Bridge. The tolls were abolished in 1864. The bridge limped on

into the 20th century. To be fair judging by photographs showing the

bridge it was not a bad looking thing at all. Still it was living on borrowed

time and the new bridge, the current bridge, was constructed between 1913 and

1921.

Southwark Bridge has five steel arches supported by granite

river piers. On top of the piers on each side of the bridge are alcoves for

pedestrians to sit and take a break. This echoes a feature of the last phase of

old London Bridge, which I’ll say a little more about when I get there. All in

all the current Southwark Bridge is a perfectly decent river crossing, however

it does hold the unenviable record of being the least used of all of the Thames

bridges in London.

Cannon Street Railway Bridge

The last railway bridge downstream in London is this, Cannon Street Railway Bridge. Cannon Street station was built to give the South Eastern Railway a terminus within the City of London. This necessitated the building of a bridge to carry the railway. Designed by Sir John Hawkshaw and opened in 1866. It had five spans supported by cast iron pillars. It was originally called the Alexandra Bridge, the Prince of Wales having only recently married Alexandra of Denmark. It had two footpaths that were removed in the 1890s so that the bridge could be made wider.

The bridge was damaged during world war II and had to be partially

rebuilt. Then in the 1980s British railways carried out an extensive renovation

and removed much of the ornamentation on the superstructure. Thankfully they

left the two original brick towers facing onto the waterfront on the City side.

There it is, not a lot more that I think I can say about it.

London Bridge

Here I think I should declare an interest. A couple of decades ago I read Patricia Pierce’s excellent book about Old London Bridge and thought to myself – I bet that would make a good Mastermind subject -. In 2007 it did. I used it as my specialist subject in the grand final. So once I start going on about old London Bridge I find I really easy to get carried away with my subject. I will do my best to try to keep this relatively brief.

Nobody knows exactly how many wooden bridges were built

here across the Thames after the Romans built the first around 50AD. During the

reign of King Ethelred II (nicknamed the Unready) the story goes that one of his

allies pulled down the then bridge to thwart the Danish armies. This was

commemorated in a poem by skaldic poet Ottar Svarte, and some people believe

that this poem, the first lines of which translate as

‘London Bridge is broken down,

Gold is won and bright renown’ – is actually the origin of

the nursery rhyme London Bridge is Falling Down.

The decision to rebuild London Bridge in stone was taken

during the reign of King Henry II and work began in 1176, under the direction

of local parish priest Peter de Colechurch. It was completed in the reign of

King John in 1209. Although we don’t have any images or written descriptions of

the bridge at the time it’s most likely that it had buildings on the

superstructure right from the start. Buildings on the bridge were demolished or

destroyed and rebuilt for over 500 years until the extensive remodelling from

1758 - 1760 when all the buildings were

removed. There was a fortified gateway at the southern end, where severed heads

were displayed after the drawbridge gate was demolished. The drawbridge itself

could be raised twice a day to let ships through, although it ceased to

function and was made solid in the remodelling at the start of the fifteenth

century. The most notable feature of the bridge until the 16th century was the

Chapel of St. Thomas a Becket. Becket was the patron saint of the City of

London and had actually been a parishioner of Peter de Colechurch. The chapel stood

on the thickest pier, just over halfway across from the Southwark side. During

the Tudor reformation Henry VIII had the chapel demolished. During the reign of

Henry’s daughter Elizabeth I a partially prefabricated timber house, probably

manufactured in the Netherlands, had large parts of it ferried to the bridge,

where it was erected. It was called Nonesuch House and it stood in increasingly

dilapidated condition until all the buildings were removed from the bridge.

A number of interesting events punctuate the bridge’s

history. The current London Bridge and several other Thames bridges are cared

for by the Bridge House estates. This is a charitable organisation and dates

back more than 900 years, predating old London Bridge itself. There have been

times when the old bridge was taken out of their care. Notably King Edward I

gave over the care of the bridge to his mother, Eleanor of Provence – who is believed to be the my fair

lady of the nursery rhyme. She proved expert at gathering the tolls, but not so good at using them on

the maintenance of the bridge. During her stewardship part of the bridge

collapsed. Maintenance of the bridge was a problem throughout its 600+ year

history. It had 19 narrow arches, which greatly reduced the width of the river

in real terms and meant each pier was under huge hydraulic pressure.

If you were coming from the Continent the only way to get to

Westminster or the City of London was by taking a water ferry, or by crossing

London Bridge. So it was the scene of a great deal of pageantry, and not a little

bloodshed. In 1381 the leaders of the Peasants Revolt threatened to set fire to

the bridge if the citizens did not lower the drawbridge to let the ‘peasant

army’ cross. Later on in Richard II’s reign it was also the scene of a magnificent

joust between the champions of England and Scotland. (Scotland won 1-0)

The Chapel of Thomas Becket was often used as the starting

point for pilgrimages to his tomb in Canterbury Cathedral and the chapel was

rebuilt in about 1400 with money from the charitable bequest of the real Lord

Mayor Dick Whittington. During Jack Cade’s rebellion in the reign of Henry VI

the rebels were defeated in battle on London Bridge itself.

I’ve already mentioned the nineteen narrow arches. In the

mid 18th century remodelling when all of the houses were remove from

the bridge the two central arches were combined to make one ‘great arch’. This

did not prevent the Thames from freezing over during particularly cold winters

and in 1814 it caused the last of London’s Frost Fairs. When the thaw came the large

chunks of ice shooting through the arches caused a lot of damage to the bridge

and within a few years it was accepted that the bridge would have to be

replaced. Demolition didn’t actually start until after the replacement bridge

opened slightly downstream in August 1831.

There are remnants of Old London Bridge you can see if you

know where to find them. In the 18th century remodelling, some of

the piers were topped with curved alcoves. When his Dad was imprisoned in the

Marshalsea Prison young Charles Dickens used to go and sit in these to watch

the world go past him. You can find one of these in the grounds of nearby Guys’ Hospital and another 2 in Victoria Park in Hackney. The Museum of London

has smaller remains on display too. The church of St. Magnus the Martyr on the

Northern bank of the Thames was actually the start of the roadway onto the

bridge and the churchyard has several blocks which were part of the bridge

which were uncovered during work on a nearby building in the 1930s.

Right, that’s the old bridge, which is the longest lasting

and for me the most interesting bridge ever to span the Thames. Now we come to

Rennie’s Bridge. Rennie’s design was one of five that were considered, eventually

winning approval. The foundation stone was laid in 1825. Rennie died four years

earlier but work on the bridge of five stone arches was carried out under the

direction of his son, another John Rennie. For the first few decades after its

1831 opening many people expressed admiration for the bridge and the way it

dealt with traffic far better than the old bridge had ever done. Still, it was

probably unrealistic to expect that John Rennie, designing the bridge in the

second decade of the 19th century could possibly foresee the

exponential increase in traffic over the second half of the 19th

century. By the end of the century there was a desperate need for the capacity

of the bridge to be increased and it was widened. Within a few years surveys

revealed that the bridge was subsiding by an inch every eight years, with the

east side subsiding more severely than the west side.

Hence the decision to replace the bridge. It was a man

called Ivan Luckin who proposed the idea of selling the bridge. Despite initial

scepticism from the City Council the bridge was put on the market in 1968. On the 18th

April it was bought by US oilman Robert P. McCullough who envisioned it could

be the centrepiece of his Lake Havasu resort.

There is an urban myth that Robert McCullough thought he

was actually buying Tower Bridge. There is a word for this. It’s cobblers. Mr.

McCullough was fully aware of what he was buying. During negotiations there was

even a scale model of London Bridge on the table in front of him. So the stones

of the bridge were numbered, dismantled, shipped off to Lake Havasu and rebuilt

there. Well, sort of. Some of the stones were certainly numbered and shipped

off. Not until after they had been shaved so that they could be fitted as

facing stones over the new concrete frame which had been built to hold them. A

lot of stone was sold off and a lot was just let in an abandoned and flooded

quarry. A very large number of souvenirs were made from discarded stones – I myself

have a small block, an ash tray and a desk set.

The current bridge was built while Rennie’s was being

demolished. They would work on for example the upstream side while the

downstream side would continue to be open to traffic, then vice versa when that

side as finished. Finally it was opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1973.

So, the current bridge consists of three spans of

prestressed concrete box girders. Nope, me neither. From the river side, well,

it looks alright if you like concrete, I suppose. Its bland. On anything except

the sunniest day its sides look grey and miserable. No, in order to get the best

view of the bridge you need to get up on the walkways.

Wide, isn’t it? It carries 6 lanes of traffic across the

river. I’ve seen a number of websites claiming that Wandsworth Bridge is London’s

busiest but I wouldn’t be surprised if London Bridge gives it a fair old run

for its metaphorical money. London Bridge at the time I’m writing this is only

fifty one years old, and I reckon it will need to be at least double that age

before we can really start to decide whether it has stood the test of time. But

based on what we’ve seen since it opened, I’d say it scores highly for

functionality. For aesthetics? Nah, not so much.

|

| Old London Bridge - the most remarkable bridge ever to cross the Thames ( or any other river in my opinion) |

Tower Bridge

So our journey ends where my 1982 journey began, at Tower Bridge. When you talk or you write about Tower Bridge as a bridge you’re up against the fact that Tower Bridge isn’t just a bridge. It’s a world landmark and it’s also a symbol. For many years as a teacher, in my first lesson with a new year 7 class I would draw several symbols on the board to show the kids things about me, if they could work them out. For example I would draw a stork with a bundle and ‘x5’ to show them that I have five children. To show them that I come from London I would draw a simplified outline of Tower Bridge. And to be fair, it nearly always worked. For Tower Bridge transcends its existence as a mere river crossing. It is nothing less than a symbol of London. There are two structures which evoke in me a feeling of pride in London and a nostalgia for growing up there. The dome of St. Paul’s is one, and Tower Bridge is the other.

Through the second half of the 19th century the development of the East End led to increasing demand for a new bridge downstream of London Bridge. The opening of Rennie’s London Bridge in 1831 led to a huge increase in traffic, so much so that London Bridge would need to be widened in 1901, and the need for a new bridge to relieve the congestion became more pressing throughout the 1870s. An 1876 report recommended the building of either a new bridge or a new tunnel to the east of London Bridge. More than fifty designs were submitted, but in 8 years all that the committee of the Bridge House Estates had managed to do was to decide that the bridge would only be one of three designs of 2 types – either one of two designs of swing bridge, or a bascule bridge. A bascule bridge was decided upon, and an act of Parliament passed to the effect in 1885.

The Act imposed some stringent conditions on the design of the bridge. Boiling these down to essentials, the bridge would have to ensure that it was no obstacle to tall ships passing into the Pool of London to load and unload at the wharves on the Southwark side of the river. Also, the design of the Bridge had to match the architecture of the Tower of London. There was also a stipulation that the construction of the bridge had to be completed within four years. This necessitated a further two Acts of Parliament to extend the timescale of the construction.

Horace Jones as architect and Sir John Wolfe Barry as engineer designed the bridge in a way that fulfilled the conditions of the Act of Parliament. Jones died before the completion and Barry took over as architect as well as engineer. In Jones’ original design the façade was meant to be red brick but the changes to a more ornate Victorian Gothic style were thought to be more in keeping with the Tower of London.

Tower Bridge was a target for enemy bombing raids during the Second World War and although it was fortunate enough to escape a devastating direct hit it did suffer damage on a number of occasions.

There are few more archetypal London experiences for which there is no charge than standing by the river either a little upstream or downstream of the bridge and watching the bridge being raised and lowered. If you’re visiting London you have a pretty decent chance of being able to do so because the bridge currently is raised about a 1000 times a year. Which is considerably less than the first 12 months of its operation, when it was raised over 6000 times. To be fair at that time the Port of London was probably the busiest in the world so there was a lot more traffic on the river.

Coming back to the untrue urban myth about Robert P. McCullough believing he was buying Tower Bridge, which we discussed along with London Bridge, the origin of this possibly lies in the fact that many people other than Londoners, do actually think that Tower Bridge is London Bridge. I can sort of understand this. London Bridge has the history, the famous name, the song. But it really doesn’t look the business. Tower Bridge looks the part. So, not London Bridge, no. But London’s Bridge, yes, that I can get on board with.

--------------------------

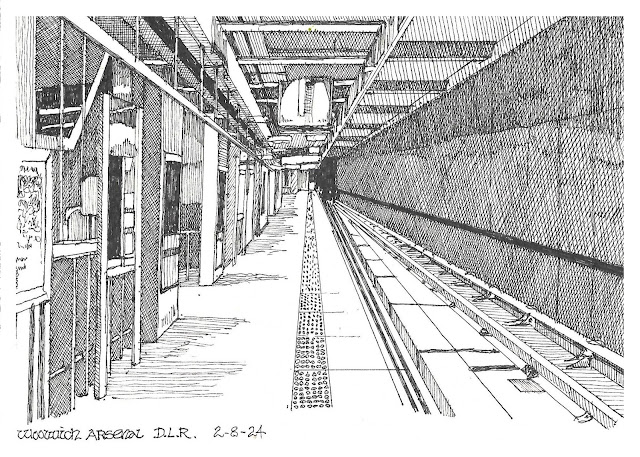

If you were kind enough to follow what I wrote about

drawing all of the stations on the London Underground, then you might remember

how I went on to extend the challenge to include every station on the London

Overground and the Docklands Light Railway. It’s okay if you didn’t, I can’t

say that I blame you. Well, a similar thing has occurred to me that I should extend

this challenge to include all of the tunnels beneath the Thames in the Greater

London area.

Well, I say all of them. I don’t actually mean tunnels

which have only ever carried utility cables. There are nine of these that I

know of in the specified area. However there are 17 tunnels that have carried

the public in one form of transport or another, only one of which no longer

does so. These are the ones I want to work on.

Drawing tunnels, however, is by no means as straightforward

as drawing bridges. So I’ve had to think about the ways I want to do it. The

foot tunnels (and the tower subway) are easy enough, since I will draw the

entrances. The road tunnels, ditto. The train tunnels, well, this calls for a

little more thought. If you’ve ever travelled in a tube train you’ll know that

there really ain’t a great deal to see in the tunnels themselves. So what I

plan to do is to sketch the exterior of a station at either end of the tunnel,

or the platform of the station. Is that acceptable to everyone? Well, I shan’t

lose any sleep over it if it isn’t because that’s how we’re going to do it.

Victoria Line tunnel – Vauxhall to Pimlico

I once gave myself a challenge to draw every London Underground Station. This was before lockdown and it seems like a lifetime ago, even though I wasn’t much more than five or six years ago. One of the things that struck me during the challenge was how few stations there are south of the river. Even with Battersea Power station and Nine Elms opening since, there’s still only about 30. Maybe that sounds like quite a few. Not when you consider there’s about 240 north of the river. I guess that’s one reason why there’s relatively few bridges which carry the Underground across the river. However another reason is that there’s quite a few tunnels and the first transport tunnel that we encounter on a journey working downstream from west to east is a London Underground tunnel. This carries the Victoria Line from Vauxhall to Pimlico.

Pimlico is interesting because it wasn’t on the original

plans for the Victoria Line, which meant that it was the last to open. This may

account for the fact that all of the other stations on the Victoria Line also

connect with at least one other line, but Pimlico doesn’t. Pimlico does at

least serve people visiting the original Tate Gallery, Tate Britain.

*Digression Warning* I grew up in the London Borough of

Ealing and one of the things my home borough is renowned for is Ealing Film

Studios. In the immediate post war period Ealing studios made a series of

comedy films which were extremely successful and one of the most famous of

these was called “Passport to Pimlico”. Basically the plot concerned the

residents of Pimlico finding that Pimlico had been given to the Dukes of

Burgundy in the middle ages and this had never been repealed. Said residents

then throw away their ration books and assert their independence. Allowing for

the way that a nation’s collective sense of humour can shift over the decades it’s

a funny film, but one which also manages to make a point about post war

austerity in the Britain in which my parents grew up.

At the other end of the tunnel is Vauxhall Station. Back in the good old days when I was cycling past the station on my way between home and university, old Vauxhall station really wasn’t a lot to write home about. It’s still there, but what has grown up around it is remarkable. Vauxhall has become a huge transport hub, and the entrances to the subterranean tube stations are visions of the future in chromium and glass. I’ll be honest, when work was going on a couple of years ago and I was visiting London with my daughter and grandson we took a double decker bus from Wimbledon to Vauxhall Bridge and I found the whole scale of the tube and bus station complex rather oppressive. That’s just a personal opinion and please feel free to disagree.

Jubilee Line Extension tunnel – Waterloo to

Westminster

No fewer than three cross river tunnels serve Waterloo station, each of them bearing a London Underground line. The furthest upstream is the Jubilee Line tunnel to Westminster station.

The Jubilee Line section of Westminster station opened in

1999 and I visited it within a year of the opening. This was the London

Underground Jim, but not as I knew it. Once you go through the entrance you are

struck by the fact that this is by no means a beautiful station, but my

goodness, it has a scale that inspires admiration. The elevators to the deep

level Jubilee Line platforms are supported by columns and even today to ride

them is to experience what early 20th century visions of the city of

the future thought it would be like.

In the original plans for the Jubilee Line it was never

envisaged that the line would pass through Westminster. When the time came at

the end of the 20th century to make the Jubilee Line extension the

decision was made to connect with Waterloo station, and a tunnel between a new

deep level Westminster station and Waterloo seemed the best way of doing it.

I’ve used metros and subways in many European countries,

and Westminster station reminds me quite a lot of an archetypal European Metro

station. Only the Jubilee Line on the London Underground has automatic doors

allowing passengers to access the trains and this is far more common in Europe.

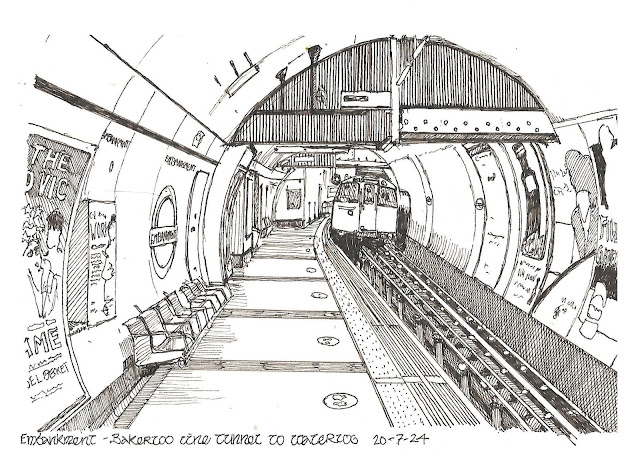

Bakerloo and Northern Line Tunnel – Waterloo to

Embankment

Strictly speaking the next transport tunnel downstream is actually two separate tunnels. I fact it's four really. I’m lumping them together because they both go from Waterloo Underground station to Embankment Underground Station. The Bakerloo line tunnel(s) was built first in 1906, while the Northern Line tunnel(s) was built 20 years later.

The Bakerloo Line of the London Underground began life as

the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway. According to various sources they had the

devil’s own job raising finances, eventually selling out to Charles Tyson

Yerkes' Underground Electric Railways of London, laying the foundations for what

would eventually become London Transport.

The tunnel benefited greatly from the experience of building deep level tube lines which had been gained by the engineers of the City and South London Railway, the world’s first deep level underground railway. It used the Greathead tunnelling method. Greathead adapted the tunnel shield invented by Marc Brunel (more on him later) for the Thames tunnel. Instead of having brick walls built up behind the shield as it was cut and pushed forward, the tunnel linings were made of cast iron rings bolted together. Greathead had used the system first when building the Tower Subway - we'll get there, don't worry.