In April 2024 I made a drawing based on an old photograph of a horse bus in the Old Kent Road. It set me off on a train of thought which led to me challenging myself to make drawings of every property, station and utility on the traditional London Monopoly Board. I have allowed myself to include sketches I've made in the past as well as new ones. So this is where I am at the moment:-

1) Old Kent Road

The Old Kent Road is the only property south of the River Thames. It goes through many changes of name, but if you follow it, then it will take you all the way to Canterbury - I know because I cycled it in a day once. It was home to the venerable Thomas a Becket pub, which was on the site where Chaucer and his pilgrims made their first stop on their pilgrimage in The Canterbury Tales.

2) Whitechapel

The name Whitechapel might well make you think of the Whitechapel Murders, the atrocities committed in the area by the individual known as Jack the Ripper. However Whitechapel was also home to the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, one of the oldest commercial businesses in the UK until its 2017 closure. Arguably the 2 most famous bells in the world, Philadelphia's Liberty Bell, and London's Big Ben were both cast in Whitechapel.

3) King's Cross Station

King's Cross is not the oldest Mainline railway terminus in London - Euston just down the road is several years older. It's not the most visually striking - the Grand Midland Hotel which is part of the St. Pancras building right next door steals the attention away from its neighbour. But Kings Cross is a remarkable building. In some ways it's hard to believe that it dates back to 1852. The relative simplicity of the facade, the lack of ornamentation seem to belong to the 1920s or 30s. Having said that the Italianate clocktower between the two huge arched windows does humanise the building a little, and reminds me of a similar feature on Queen Victoria's Osborne House.

Of course, Kings Cross has a permanent place in popular culture, being the station from which the Hogwarts Express departs in the Harry Potter novels from platform 9 3/4 . There is actually a sign for platform 9 and three quarters, but you won't find the Hogwarts Express, sadly.

The horse drawn tram on the far right gives us just a little help with dating, although not necessarily as much as you might think. The first horse drawn tram in London was as early as 1861 while the very last horse drawn tram in London ceased in 1915. Like a lot of reference photos I've used in these Monopoly drawings and in other sketches of London, I would date this between the last decade of the 19th century and the first of the 20th.

One of the interesting idiosyncracies of the London Monopoly board is the choice of stations. Kings Cross makes sense and you can also make out a case for Liverpool Street. But Marylebone? And Fenchurch Street ?!? Surely Paddington, Euston and Victoria (or Waterloo) all had a greater claim. Waddingtons' Victor Watson had acquired the rights to Monopoly for the UK after his son, Norman, had acquired an American Monopoly set, and become absolutely hooked on it after spending a weekend playing. He badgered his dad, who ran the business, to acquire the rights to the game outside the USA.

Victor took what I think was a splendid decision, that the only real changes to the game that he would make were to change the names of the properties , and the money involved from dollars to sterling. It only made sense to choose London properties since these must have been better known than those of any other town or city in the UK. Apparently Victor took a trip to London with his secretary, Marjorie Philips, to scout out the locations for the UK licensed board. He was not very familiar with London, nor supposedly a great lover of the city, which accounts for what can sometimes appear to be a rather eccentric choice of properties. My West London contemporary Tim Moore - one of my favourite writers - describes this in detail in his wonderful book "Do Not Pass Go".Well, Victor Watson was from Leeds, and Waddingtons were a Leeds based company. At the time of his fact finding mission, Leeds was on the London North Eastern Railway (LNER for short). So it seems that Vic just picked the four LNER termini in London at that time.

London Monopoly Board four - Angel, Islington. The property takes its name from an inn - first documented in 1614, called the Angel. The property originally belonged to Clerkenwell Priory. The inn was rebuilt several times. The picture shows the penultimate incarnation, the Angel Hotel. This was demolished in 1902/3 and the current building was put up in its place. This too was called the Angel Hotel, but only until 1921 when it became a Lyons Corner House restaurant. The area still retained the name The Angel, though, and the nearest Underground Railway Station is still called Angel. Victor Watson and Marjorie Philips supposedly included the Angel ,Islington because they took afternoon tea in the Lyon's Corner House and enjoyed a very decent cup of Rosie there.

5) Euston Road

Even today you're not short of significant buildings to draw along Euston Road. It starts at Kings Cross. The name refers to an equestrian statue of George IV erected as a memorial on his death in 1830. So popular was George as a monarch that the statue was removed in 1845, unmourned and unmissed, much like George himself.

As I say, even today there's a lot to choose from - the Grand Midland Hotel above St. Pancras Station, the British Library and Euston Station. I've opted to use something from the back catalogue - as is my prerogative - and so we have my drawing of the Doric Arch outside Euston Station from 1837 - 1961. As I wrote when I first posted this sketch -

The first threat to the arch came in the late 1930s when a radical plan to rebuild the station was drawn up, which would have involved moving the arch at the very least. The second world war put paid to this, however it only turned out to be a stay of execution. Despite the fact that both station and arch were grade II listed, the plan for the current station were put forward in about 1960, and nobody in officialdom showed any appetite whatsoever for moving the arch to a new home. The London County Council balked at the cost, and Transport Minister Ernie Marples said all options for not demolishing the arch had been carefully examined and rejected. This was the same Ernie Marples whose company built motorways – not that he was at all biased, you understand. Pleas from great men such as Sir John Betjeman to be given time to raise the money to meet the cost of removing the arch and storing it until such time as a new home could be found for it were ignored.

Contrary to how it might seem from what I’ve just written, I do appreciate that you cannot keep things just because they have been there a long time. Otherwise we’d all be living in Bronze Age roundhouses. But I do think that there was a very strong case for keeping the Euston Arch and I point my finger at those who made the decision and rushed to demolition, and am happy to say that you have let down the people you were working for and sold all our birthright for a mess of concrete.

6) Pentonville Road

7) Jail

Newgate prison was established by King Henry 2nd in 1188. It came to take over part of the original Newgate, a ceremonial fortified gateway leading into the City of London. Amazingly Newgate Jail was still operating right at the start of the 20th century, though it closed in 1902 and was demolished a year later.

Charles Dickens had a thing about prisons. It’s not surprising when you consider that his father John Dickens was imprisoned in the Marshalsea for a period during Dickens’ childhood. The Marshalsea is the backdrop to “Little Dorrit” and other novels he wrote feature episodes in the Fleet Prison and also the Kings Bench Prison. However Newgate recurs throughout his writing, from an early article in “Sketches by Boz” through “Oliver Twist”, right up to “Great Expectations”, arguably his greatest work. His first historical novel “Barnaby Rudge” concerned the Gordon Riots, during which Newgate was attacked and partially destroyed.

Waddingtons (sensibly in my opinion) decided to change as little as possible about the original board, and did very little other than replacing the names on the properties with London locations and the dollar prices with sterling. Free parking used an American jalopy, while the policeman ordering the unlucky player to go to jail looks about as British as the Stars and Stripes or the Statue of Liberty. This is probably why Jail (just visiting) and Go To Jail are spelled thusly rather than the more traditionally British spelling Gaol. Some experts believe that Monopoly certainly helped this Jail spelling become far more commonly used in the UK.

Jail is an example of Victor Watson's approach to the original Monopoly board. Which I think can be quite neatly summarised as - if it ain't broke, then don't fix it.

8) Pall Mall

Aren’t word derivations fascinating? If your answer is no

then you might want to skip the next few paragraphs.

Our 8th stop on the London Monopoly Board is

Pall Mall. The three properties in this pink set are linked by being

thoroughfares radiating from Trafalgar Square. Whitehall is a major

thoroughfare, Pall Mall and Northumberland Avenue, less so.

Pall Mall takes its name from the Italian game pallamaglio.

The game was in some ways similar to croquet, because it involved hitting balls

with mallets. The literal translation on the Italian is ball-mallet, and it’s

clear to see how the Italian mutated into pall mall, the English name of the

game. Charles II was fond of the game, which was played on a long, narrow rink,

and so he had Pall Mall laid out so that he could stroll over from the nearby

Palace of Whitehall for a leisurely game. Samuel Pepys mentions it in his

diary, where he calls the game pell-mell. Nowadays to do something pell-mell

means in a rushed and disorderly fashion. Sounds like the game would have been

more unruly than croquet.

Pall Mall eventually developed with commercial properties and Gentlemen’s clubs. The name Mall thus became applied to many long, straight

roads containing shops and commercial premises. From there, it’s only a small

hop to applying the name to a building containing shops and outlets.

I used to think that Pall Mall and The Mall were the same

place. No. The Mall is the long, wide road leading from Trafalgar Square to

Buckingham Palace and the idea of developing the road with buildings or hotels

is pretty unthinkable. Maybe the fact that Pall Mall was home to some of London’s

most famous and exclusive Gentlemen’s Clubs appealed to Victor Watson. Then again,

maybe he was influenced by the fact that Pall Mall was, and is, the name of a

well known brand of cigarette. It’s surprising how many properties on a London

Monopoly Board are or have also been the names of cigarette brand. Off the top

of my head, Pall Mall, Strand, Piccadilly, Bond Street, Park Lane and Mayfair

have all been cigarette brands at one time or another. Not to mention Marlboro.

Yes, Marlboro, a cigarette brand which could not be more American if it tried,

was actually named after (Great) Marlborough Street, where the Philip Morris

company had its cigarette factory!

9) The Electric Company

I was tempted to use a picture I sketched of Battersea Power Station a few years ago for the Electric Company. But Bankside is closer to the centre of London, and has a more remarkable story. Before the 21st century, London's Bankside Power Station was the kind of building that Londoners either tried to ignore, or to pretend that it wasn't there. Directly across the Rover Thames from St. Paul's Cathedral, and just a stone's throw from where Shakespeare's Globe Theatre once stood, the Bankside Power Station provided electricity for London from 1891 until 1981, although the current (should you pardon the pun) building only dates back to 1947. Decommissioned in 1981 the future of the building looked very much in doubt until, in 1994 London's Tate Gallery announced that the building would become the permanent home of the Tate Modern Art Gallery. The Tate Modern opened in 2000, and is now one of the most visited buildings in the whole of the UK.

The Tate Modern is one of the largest and most important collections of Modern and Contemporary Art in the world. I have visited it once, but I'm afraid that my visit only served to confirm what I have always suspected - that when you get right down to it I'm a bit of a philistine. Particularly when it comes to abstract art, while I can appreciate skill, and occasionally respond emotionally, when you get right down to it I don't really get it. I'm willing to accept that this is down to my own aesthetic deficiencies. It still doesn't change the fact that I don't get a lot of it though.

I thought I'd use a variety of different coloured fineliners and see what sort of effect I could get with them.

Whitehall

is a thoroughfare connecting Trafalgar Square to the Houses of Parliament in

the Palace of Westminster and to Westminster Bridge. The thoroughfare passes

through some of the area formerly occupied by the royal palace of Whitehall,

hence the name, and was the monarch’s principal residence within what we now

think of as London from the reign of Henry VIII until it burned down in 1698.

It was called the White Hall because of the stone from which it was originally

built.

Nowadays

Whitehall is a term which doesn’t just apply to the Street. Whitehall Palace

was the centre of Government administration from Henry VIII’s time, and this

continued even after the Palace burned down since many Government ministry

headquarters were sited along Whitehall, and some still are. So the word

Whitehall can also refer to government policy and to the Civil Service, who

administer it.

Coming back

to the thoroughfare, there’s lots of notable things associated with it as well

as the Ministry buildings. Whitehall is where the Cenotaph stands, and the

Remembrance Day Ceremony takes place. The entrance to Horseguards Parade is

always flanked by ceremonially dressed members of the Household Cavalry. Downing

Street, home of the UK Prime Minister, can be accessed from Whitehall, but only

if you have a pass. Just off Whitehall, linking it with Northumberland Avenue,

is a street called Great Scotland Yard, where the original headquarters of the

Metropolitan Police Force were located. Whitehall itself is punctuated with

half a dozen statues and memorials, most of which commemorate figures from the

history of the British Armed Forces.

11) Northumberland Avenue

Northumberland

Avenue is a relatively short thoroughfare which links Trafalgar Square with the

Embankment. It’s one of the youngest streets on the London Monopoly board. Pall

Mall was laid out in the 1660s, and Whitehall was laid out following the burning

down of Whitehall Palace right at the end of the 17th century.

Northumberland Avenue was built between 1874 and 1876. It was built on the site

of the former Northumberland House, the London home of the Percy family, the

Dukes of Northumberland.

It's always

struck me as a continental style Avenue whenever I’ve had cause to frequent it.

Partly this is because although it’s short, it’s also very wide. This was a

method the developers used to get around local building and planning

regulations that stipulated that hotels must not be built taller than the width

of the road they were on. Notable amongst these was the Hotel Metropole, which

still exists, but under another name. Prince Albert Edward, the future King

Edward VII was very fond of it. The building is notable for its striking wedge

shape.

Another

interesting building is a preserved cabmen’s shelter. Laws in London in the 19th

century stipulated that horse-drawn cab drivers could not leave their cab while

it was on a cab stand. The cab shelter fund – which still exists to maintain

the shelters - was established to build shelters for cabmen so that they could

get a hot meal without risking their cabs being stolen, and that they had less

of a risk of freezing to death in the depths of winter. At one time these

distinctive little green buildings were a fairly common sight in London. There

were more than 60 of them. I remember one in Ealing Broadway when I was growing

up in the 70s. That’s gone, although it has been replaced by a new structure

which is obviously inspired by the cabmen’s shelter. There are only 13

remaining now, but each one is a listed building.

12) Marylebone Station

Marylebone Station was the last of the London Railway termini to be built. In many ways it is the poor relation amongst them, having nothing like the grandeur of Kings Cross, St. Pancras, Paddington and the original Euston to name but a few but nevertheless I do have a wee bit of a soft spot for it. One reason is because it's the station the Beatles are chased through in their first and best film, A Hard Day’s Night. Another reason is that it was a project pushed through by one of my favourite crusty old Victorian/Edwardian curmudgeons, Sir Edward Watkin.

Sir Edward was chairman of several railways, most notably the Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first Underground railway. Watkin did not like the fact that another of his railways, the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, had no line into London, and thus lost valuable traffic to the Great Northern from King’s Cross. He eventually obtained permission to extend the MSLR – now called the Great Central Railway – into London, at Marylebone. The station opened to traffic in 1898. The Great Central Railway became part of the London North Eastern Railway in the 1923 rationalisation of most of the railways in Britain into four large companies – the London Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), the Great Western Railway (GWR), the Southern Railway and the LNER. Which is why Marylebone was chosen by Vic and Marjorie for a Monopoly Station – all four they chose were LNER termini.

By the 1980s Marylebone was a serious candidate for closure. This was due to its quietness compared with other large London stations. This is what has made it so popular with film makers over the last few decades – Marylebone has probably been a named or unnamed location for filming more times than any other mainline station in London.

Coming back to the great curmudgeon Edward Watkin, he delayed the building of London’s Circle Line for a good couple of decades just because he didn’t like the chairman of the Metropolitan District Railway – James Forbes. This despite the fact that it would have increased revenue for both railways.

He's probably best remembered for attempting to build London’s answer to the Eiffel Tower on the site where Wembley Stadium now stands. The Tower only reached its first stage before it was found that changes to the original design meat that the legs were unstable. Work was stopped for good shortly before Watkins’ death in 1901 and the whole thing was dynamited and demolished by 1907. Aerial photographs of the building of the original Wembley Stadium in the 1920s clearly show where one of the footings had been on the area where the pitch was laid.

The naming of the street is a little confusing because it’s in the centre of London, and not really near the area of Bow at all. Bow street is actually very close to Covent Garden, the former fruit and veg. market, which is now London’s unofficial capital of street entertainment.

Prior to being included amongst the orange set of properties on the London monopoly board, Bow Street was possibly most famous for being the home of the Bow Street Runners. This was a forerunner of the first police forces, a group of volunteer law enforcement officers founded by the London magistrate and novelist Henry Fielding. They were disbanded soon after the formation of the Metropolitan Police force. All of the properties in the London orange set have connections with the law and law enforcement. Courts were held in the homes of city magistrates on Bow Street – including Henry Fielding – and between 1878 and 1881 the current building which house the Magistrates Court – one of the most famous in England – and Bow Street Police Station was built. The Police Station closed in 1992 and the last case was heard in the court in 2006. The building still stands, but since 2021 the building has housed a hotel – how appropriate! – and a museum of local police History.

14) (Great) Marlborough Street

Marlborough Street.

As a quiz question master I have in the past asked the

question – which street on the traditional London monopoly board does not

actually exist in real life – the answer to which is Marlborough Street. This

is because it has never been called just Marlborough Street, but rather Great

Marlborough Street. A bit of a trick question, but trust me, quizzes are full

of those.

The street is named after John Churchill, the first Duke of

Marlborough, and in the view of Queen Anne, he was pretty great. It was first

laid out in 1704, during her reign. Like Bow Street, Great Marlborough Street

was home to one of the most important Magistrates’ Courts in London. This

closed in 1998.

One of the most remarkable things about the street is that it gave its name to the Marlboro cigarette brand. Makers Philip Morris had a factory on the street at one time, and used an americanised version of the name for a cigarette brand that consciously plays on the image of the rugged, wild western Marlboro Man. I used a modern reference photograph and this scene shows the side entrance of the famous Liberty's store, which stands on the corner of the junction between Great Marlborough Street and Regent Street, itself on the London Monopoly board.

Unlike Bow Street and (Great) Marlborough Street, Vine

Street wasn’t home to a magistrates court. However it was at one time home to

one of the busiest police stations not just in London, but the whole world.

Vine Street itself was named after a pub, the Vine. Its

possible that the pub may have drawn its name from a roman vineyard nearby, but

this is a matter of speculation. The street was laid out in the 1680s. It was

originally longer than it is now, but when Regent Street was built it bisected

Vine Street and led to one end of Vine Street becoming a dead end.

Vine Street Police station was built at number 10, and had

to be rebuilt after a fire in the 18th century. Vine Street nick, as

it was colloquially known, closed in 1940 and services removed to West London

Police station in Savile Row. Due to a rise in crime the station was reopened

in 1966, then closed for good in 1997 and demolished in 2005. Incidentally Vine

Street is one of the London Monopoly streets without licensed premises, so I’m

informed that the etiquette for a London Monopoly board pub crawl is to take a

drink in one of the hostelries on nearby Swallow Street.

In the centre of London, which contains almost all of the

properties on the London Monopoly board, there really is no such thing as free

parking. The first multi storey car park in London opened in 1901. It had space

for 100 vehicles. I’d love to know how many motor vehicles there actually were

in London in 1901. My sketch shows what is thought to be the oldest surviving

multi storey car park building in London. It stands in Wardour Street, which

runs from Leicester Square to Oxford Street. It’s now a pub.

Free Parking as a square on the Monopoly Board was

inherited from the original Atlantic City board. It’s hard to imagine that

Victor Watson would have found may free places to park when he was scouting

locations in the mid 1930s. But then Victor, clever boy, took the train into

Kings Cross on his visit, and could afford to use taxis.

I can’t afford to use taxis. To be honest, after I moved to

Wales, whenever I was visiting London in the 1990’s it was so much cheaper to

drive that I would always park the car in a residential street in Ealing, then

use public transport until it was time to go back home.

In Anglo – Saxon times the River Thames was wider then it

is now. The Strand is not very close to the northern bank of the Thames at all

now, but this is a relatively recent development. At Lundenwic’s height, the

road we call the Strand was right by the shore, hence the name.

King Alfred the Great, in the late 9th century,

ordered people out of Lundenwic and into the old Londinium. However the Strand

remained a important thoroughfare, and retained its name unchanged for well

over a thousand years.

The Strand is part of the main route linking Westminster

with the old City of London. It ends where the medieval City walls once stood.

This was marked by the gateway shown in the sketch, Temple Bar. Designed by Sir

Christopher Wren, the relatively narrow gateways caused increasing traffic

congestion and so it was carefully taken down. It was bought by Lady Meux, the

wife of a brewing magnate, and erected in the grounds of their house, Theobalds

Park. In fact I visited it in Theobald’s Park in 2003 on the day before work

began to deconstruct it and rebuild it in the shadow of St. Paul’s, just off our

next property, Fleet Street.

I used an ink sketch I made of Temple Bar a few weeks ago rather than making a new one. I felt a bit guilty about this so I made a direct watercolour sketch instead

18) Fleet Street

Allow me to indulge myself with a little more Old English.

Fleet derives from the river Fleet, one of London’s lost rivers. The word fleet

derives from the Old English fleot, which has several meanings, one of which is

stream.

The Fleet ran in the open from Hampstead down through

London to join the Thames. Fleet Street was originally called Fleet Bridge

Street, since the road was bisected by the Fleet. By the 1870s the whole course

of the Fleet was covered over.

Fleet Street runs up Ludgate Hill past St. Paul’s

Cathedral. There are many interesting stories about St. Paul’s, and its

destruction in the Great Fire and subsequent rebuilding. Many people have read

Samuel Pepys accounts of the fire, and very informative they are too. However

if you’re interested you should also have a look at John Evelyn’s diary too. I

like the story that Christopher Wren visited the burnt out shell of the old

cathedral and found a broken stone with the word ‘resurgam’ which of course means

I will rise again.

Fleet Street was also the home of the (probably) fictional

Sweeney Todd, the barber who killed his customers and had them baked into pies.

I say probably fictional. There have been some claims he was a real person, but

there’s been nothing I’ve ever seen that would stand up in a court of law.

In the 19th and especially the 20th

centuries Fleet Street became synonymous with the newspaper industry and was

home to most of Britain’s national newspapers. They’ve all moved out to

pastures new now. Although the newspapers have gone, some printers still

remain, maintaining an association with Fleet Street that goes back to 1500,

when Wynkyn de Worde, the apprentice of England’s first ever printer, William

Caxton, first set up his press here.

19) Trafalgar Square

The name Trafalgar Square references the 1805 Battle of

Trafalgar. What is now the square once housed the Royal Mews, until King George

IV moved the mews to Buckingham Palace in the 1820s. John Nash was asked to

develop the site, but he died and work progressed very slowly. In 1830 the site

was going to be called King William IV Square after his accession that year.

Finally in 1835, the 30th anniversary of Trafalgar, it was decided

to name the square Trafalgar Square, and include a memorial to Nelson. One can

guess that the owner of the square, King William must have been enthusiastic, bearing

in mind that he had been a brother officer and a personal friend of Nelson during

his own time in the Navy.

The Square wasn’t opened until 1844. Its most well known feature

is Nelson’s Column, a 145 feet tall Corinthian Column topped with Edward Hodges

Baily’s statue of Nelson. This has become one of London’s most iconic and recognisable

landmarks. The base of the statue is flanked by four pedestals, each bearing a

bronze statue of a lion, sculpted by Sir Edwin Landseer.

Throughout its history Trafalgar Square has seen a huge number

of mass gatherings and demonstrations. It became the unofficial focus of London

New Year celebrations, and I remember dancing in the fountains on New Years Eve

in the early 80s very fondly. I remember the 2 hour walk home sopping wet less

fondly. The Square is still home to a large number of pigeons. Up until the 21st

century feeding the pigeons in the square was seen as an essential component of

any visit to London. Then people began to realise the public health risk of a

gathering of 35,000 pigeons in such a small space. Feeding the pigeons has been

banned since the early 2000s.

There are four plinths surrounding the square. Three of

them have permanent statues – George IV, General Charles Napier and General

Henry Havelock. The fourth plinth was unoccupied until the 21st century,

since when it has been used for temporary displays of sculpture by some of the

leading names in contemporary sculpture in the UK and the rest of the world.

Let’s come back to Nelson. In July 2020 protestors in the

city of Bristol pulled down a statue of the 17th/18th

century trader Edward Colston. The statue was supposedly erected by a grateful

city, as a way of memorialising his charitable support of almshouses, churches,

workhouses and schools. The protestors’ argument was that in our modern,

multicultural Britain, glorifying a man who organised and greatly benefited

from the Slave Trade is untenable. To me, that makes sense, bearing in mind that

the city authorities seemed unwilling to even enter into a dialogue on the subject.

This action focused public attention on the question of public memorials to men associated with the slave trade, and Nelson’s Column became the subject of public debate. This is a question which leads to very heated views on all sides. The older generation as a rule don’t even want to discuss it – my mother and stepfather both being examples.

Look, I’m a Londoner myself, and I get an emotional buzz whenever I see an iconic image of the city like the column. But. . . Symbols matter. Images matter, and the messages that they convey matter.

Now, as I understand it Nelson did not own slaves. As far

as I know Nelson did not trade in slaves. Okay. However, he was certainly

opposed to Wilberforce’s campaign to abolish the slave trade, and he seems to

have been very friendly and protective towards the slave owning elite in the West Indies. I’m not saying this in itself means we should convict him and tear

his statue down at once. But I am very much saying it is at least grounds for a

constructive public debate on the subject. If Nelson was as great a hero as his

defenders think he is, then his reputation will survive any amount of public

debate. But if he wasn’t, then we certainly should be discussing it.

There aren’t many London Monopoly Board properties that I

have never visited in real life. In fact Fenchurch Street station is the only

one. Well, I've never been in a waterworks I suppose, so make that two. But let's stick with Liverpool Street for the time being.

The world’s first railway linking two cities, the Liverpool

and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830. The railways reached London in 1836, with

the opening of London Bridge station. By the middle of the 1830s new railways

were booming and would go on booming for 10 years until the crash of 1845.

Everyone wanted a piece of the pie and although the majority of planned railways

in this period were never even built, a large number of companies had their eyes

on London.

Fenchurch Street Station was built in 1841, for the London

and Blackwall Railway. Through acquisitions and mergers it served a number of different

railway companies. When the vast majority of Britain’s railways were

rationalised into four companies in the 1920s,Fenchurch served the LMS (London,

Midland and Scottish Railway) and the LNER (London North Eastern Railway). This

is why it’s included on the London Monopoly board, as an LNER terminus.

Fenchurch Street is the only London terminus which is not

also a London Underground station. In the 90s it was planned to either connect

Fenchurch Street with the Jubilee Line or to extend the Docklands Light Railway

a few hundred yards to Fenchurch Street, which would put it onto the network,

but neither of these plans came to fruition. Fenchurch Street largely connects

the City of London with Essex. The current building dates back to 1854.

So we now move on to the yellow set of properties, the

third most exclusive on the London board. Like the red set, these are linked

geographically but they are also linked thematically as the orange ones are,

being associated with nightlife and entertainment. Well, I wouldn’t know a lot

about nightlife but Mrs. C and I had our first date in the Odeon cinema there. Leicester

Square is very much an entertainment hub nowadays. London’s biggest cinemas are

clustered around the square, and it is the venue for more film premieres than

all other locations in the UK combined. Leicester Square is at the heart of the

‘West End’ of London, the theatre district. It’s also home to many restaurants,

and is noted for Chinese cuisine, bordering as it does on Soho’s ‘Chinatown’.

Like Pall Mall. Leicester Square came into being during the

Restoration period , just a few years later in 1670. It developed around

Leicester House, home of the 2nd Earl of Leicester, Robert Sidney.

For almost a century it was a highly genteel area, amongst whose residents

included Frederick, Prince of Wales, the father of George III. Poor old

Frederick never had much luck. He co-wrote a play which nearly caused a riot on

the first (and only) night, and lost a fortune giving the audience their money

back. Like most of the Hanoverian kings, he never got on with his father, who

refused permission for him to see his mother, Queen Caroline, when she was on

her death bed. Finally he died at the age of 44, supposedly after being struck

by a cricket or a real tennis ball.

Reflecting its connections with the theatre and later, with

cinema, the gardens in the Square contain a famous statue of William

Shakespeare and Charlie Chaplin and more recently statues have been added

including Paddington Bear, Mary Poppins, Harry Potter and Bugs Bunny. Mind you,

you’ll have to really look to find some of them, for example, Wonder Woman is

halfway up a wall, and Batman is standing on the roof of the Empire Cinema.

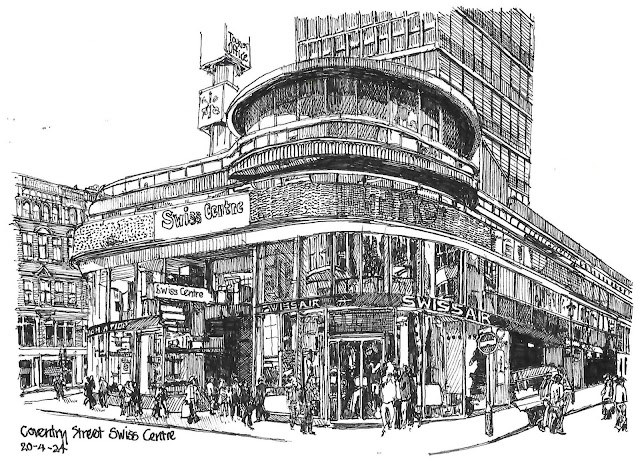

22) Coventry Street

You can walk along Coventry Street from one end to another

without even realising you’ve done so. It’s one of the shortest streets on the

London Monopoly Board. You come to the western side of Leicester Square, and

you’re near as anything already in Piccadilly Circus. Still, that short

thoroughfare you’ve just walked down between the two is actually Coventry

Street.

Like Leicester Square it does date back to the reign of

Charles II. It’s named after Henry Coventry, one time secretary of state to the

merry monarch.

For a long time Coventry Street had a seedy reputation,

with gambling houses and prostitution. In the second half of the nineteenth

century its reputation slightly improved as it became home to several music

halls. In the last century it became particularly known for restaurants and

nightclubs. Notable establishments have included the Swiss Centre, where

Coventry Street becomes Leicester Square. This was a very modern building which

lasted from 1966 until being demolished in 2007. Its most notable feature was a

carillon clock which has been preserved on the site, which is now home to the M

and M store. Coventry Street is also home to the Trocadero, which has during

its colourful life housed many attractions.

London has had many heroes throughout its almost 2000 years

of History, many of them very well known, and some of them unsung. Such a hero

was Joseph Bazalgette. He was awarded a well deserved knighthood during his

lifetime, but it’s not that well known that thousands of Londoners owed their

lives to him. It was under his direction that the sewer system was built, which

finally relieved London from the great scourge of cholera.

So, for Water Works I have chosen to draw Bazalgette’s

Crossness Pumping Station. This was a state of the art facility when it opened

in 1859. It was decommissioned in the 1950s. Ironically the building and the

machinery inside the building was only initially saved because the cost of

demolishing it, and scrapping the machinery far exceeded any value to be gained

by doing so. It wasn’t until 1970 that the building became a grade 1 listed

building – if you’re not in the UK, this means that it has the legal standing

of a building of huge national importance and virtually guarantees its

preservation for prosperity. Work on preserving and restoring the interior

began in 2008 and the building opened as a museum in 2015. The elaborate

ironwork restored in the octagon hall is worth a visit by itself.

Many people think that Piccadilly on the London Monopoly

Board means Piccadilly Circus. Well, that’s understandable. Piccadilly Circus

is probably the most important road junction in the West End. However, it is

also at the end of a mile long road, called Piccadilly. Piccadilly is a small

section of a main thoroughfare leading West out of London, connecting with the

M4 motorway.

So, let’s start with Piccadilly Circus. Throughout the 20th

century it was particularly notable for its huge neon advertisements displayed

on the side of some of its buildings. Through my childhood there was a huge one

advertising Coca Cola. The word circus in this case has nothing to do with the

type popularised by the Ringling Brothers in the USA and Billy Smart in the UK,

but simply refers to the round shape of the junction. A the other end of Regent

Street the junction with Oxford Street is called Oxford Circus. There is also a

Cambridge Circus within walking distance.

The most famous feature of Piccadilly Circus is the statue

of a winged archer. Ask most Londoners who it represents and they will

incorrectly tell you it is the Greek God Eros. Some who think they know better

might tell you that it is the Spirit of Christian Charity. Both are wrong. The

statue actually represents Anteros, the God of requited love, brother of Eros.

It stands on top of the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain. The 7th Earl

of Shaftesbury was a Victorian philanphropist who successfully campaigned to end

child labour in the UK and replace it with free education. In the 1980s

extensive repair work was done to Sir Alfred Gilbert’s aluminium statue. It had

to be removed from the square, and as work was completed put on public display

in London’s Festival Hall, where you could view it from a platform.

Bearing in mind the names of the other properties in the

yellow set you might be forgiven for thinking that the street was named after Sir Absolom

Piccadilly, King Charles II’s ceremonial bottom-wiper. However since he never

existed, this is not true. It takes its name from the piccadill. During the

time of King James I – Charles II’s grandad – a man called Robert Baker bought

land in the area and began to manufacture piccadills. If you think of portraits

of prosperous Jacobean men, like the engraving of Shakespeare at the front of

the first folio – they are often wearing broad, white cut lace collars. These

are piccadills. They probably derive their name from a Spanish word meaning

pierced or cut.

Piccadilly has been home to many grand and stately houses.

Most of these are long gone, although Burlington House still stands and is the

home of the Royal Academy of Arts. It’s also home to the very exclusive

Burlington Arcade of shops, and Fortnum and Masons. You could argue that

Fortnum and Masons are the world’s oldest department store, opening in 1707.

However they were specifically a grocers until much later. The Ritz hotel is

only one of several along the length of Piccadilly. While we’re going through

the edited highlights it also boasts the church of St. James, designed by Sir

Christopher Wren. Piccadilly Circus Underground station with its underground

circular booking hall was a pioneering achievement which caused a sensation

when opened in the 1920s. The last remaining station surface buildings were

removed at the end of the 20th century.

25) Go To Jail

When I reached Jail I decided to draw London’s Newgate

Prison. Now I’ve reached Go To Jail it only seems right to draw the Old Bailey.

After all, we know that the instruction Go To Jail means go directly to jail.

Prior to the demolition of Newgate Prison, the Old Bailey Court stood as part

of the prison complex, so it really was a direct route from one to the other. After

Newgate was demolished, the current Old Bailey building was erected on the same

site.

The Old Bailey is more correctly called The Central

Criminal Court of England and Wales. It has become known as the Old Bailey

because that’s the name of the street on which it stands. Bailey derives from

the old roman wall of the city of Londinium, and Old Bailey Street follows part

of the course of the wall.

The current building was opened in 1907. It’s possibly best

known for the statue that tops the dome. If you ask a majority of Londoners I’d

guess that they would tell you the statue is called Blind Justice. Yet she’s

not blind! It’s common to depict the personification of Justice as a young

woman, holding a sword and a pair of scales, who is blindfolded to represent

impartiality. Yet the Old Bailey statue is not blindfolded and is actually

called Lady Justice. She wears a diadem from which sun rays radiate, and looks

a bit like the Statue of Liberty’s younger sister who has given up enlightening

the world and taken up swordfighting and greengrocery.

Regent Street is named after the Prince Regent, who would

become King George IV. I have a soft spot for this particular obese royal

reprobate, not least because I took him as a specialist subject on a well known

British quiz show. Regent Street was one of the very first planned developments

of London to actually be developed. Both Sir Christopher Wren and John Evelyn

drew up plans for redeveloping the City of London under brand new street plans,

but it took so long for anything practical to be done about the plans that people

just went ahead and built new houses according to the old street plan.

The street was originally built by architect John Nash. He

was responsible for rebuilding the Regent’s elegant and sedate Marine Pavilion

in Brighton into the glorious madcap folly of the Royal Pavilion. He became so

synonymous with a particular style that George Cruikshank labelled him as “The

one wot builds the arches’ in a cartoon from 1829. Originally Nash planned a

straight boulevard, but this was impossible because of land ownership issues.

Today, Regent Street without its elegant curve at the Piccadilly Circus end

would be unthinkable, and it makes the Street one of the most instantly

recognisable of all London’s great thoroughfares.

The Green set of properties are three London streets

particularly known for shopping, and Regent Street is certainly not short on

famous stores, including Liberty’s and Hamley’s, noted in the Guinness Book of

World Records as the World’s oldest Toy shop. For a long time it was also the

largest toy shop in the world, but that record passed elsewhere in the 1990s.

Under a change of name Regent’s Street continues to Oxford

Circus, which forms the junction with the green property, Oxford Street.

Oxford Street is only one short section of one of the main

thoroughfares leading west out of the centre of London. Just about four miles

along the road it becomes Uxbridge Road, which is the main street running

through West Ealing and Hanwell, where I grew up. It follows the route of a

Roman road, the Via Trinobantia which led all the way to Hampshire. The Oxford

Street section of the road runs from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch.

Marble Arch was built by John Nash as the ceremonial gateway to Buckingham

Palace, but was moved to its present location to make room for the extension

work on the Palace in the 1850s. It’s current location was once called Tyburn,

which is where the gallows held public executions.

Oxford Street’s reputation as a shopping street largely

came about with the 20th century, and if there was one pivotal

factor in its development it was probably Harry Gordon Selfridge’s decision to

open his eponymous department store on Oxford Street in 1908. Amongst the many

distinctions the store holds, it was the venue for the first ever public

demonstration of a form of television in 1925.

Like Regent Street, Oxford Street is famous for its annual

Christmas lights and every year since 1959 a celebrity has ceremoniously turned

on the lights (not the same celebrity, obviously). Oxford Street also boasted

its own lovable eccentric for many years. From 1968 until his death in 1993,

Stanley Green paraded the street with a placard advising people to eat less

meat and reduce their libido, which would make them kinder. He also produced a

pamphlet on the subject, which sold an estimated 87,000 copies. I saw Mr. Green

once or twice in Oxford Street. I didn’t speak to him. Later I saw him

interviewed on a segment for a TV show and he came across as a very pleasant if

slightly unworldly gentleman.

28) Bond Street

Bond Street is now divided between New Bond Street, the

northern section and Old Bond Street, the southern section. But it’s still

commonly called just Bond Street. Just visually you might wonder why Bond

Street, relatively narrow and modest in appearance when compared with the

elegance of Regent Street and the wide, eternally crowded bombast of Oxford

Street, is actually the ‘boss’ location of the green set. Well, if we boil it

down to simple terms there’s a couple of reasons. Firstly, it got going as an exclusive

shopping street far earlier than the other two. It was built up by Sir Thomas

Bond around 1720. History does not reveal if he was ever shaken, or indeed

stirred. Prestigious shops were established on Bond Street throughout the 18th

century.

Secondly, Bond Street has managed to maintain this air of

exclusivity. So much so that Carl Faberge’s only establishment outside of

Russia came to Bond Street in 1910. It closed five years later due to turmoil

in Russia caused by the First World War. Bond Street is still home to upmarket

jewellers like Asprey and Garrards. It’s also the auction capital of London,

being home to both Sotheby’s and Bonham’s.

There’s a sculpture that I really like in Bond Street. It

shows what looks like a bench with two old codgers chewing the fat on it. It’s

called Allies, and the two old codgers are actually FDR and Winston Churchill.

It was erected in 1995 by the Bond Street Association to commemorate the

fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II.

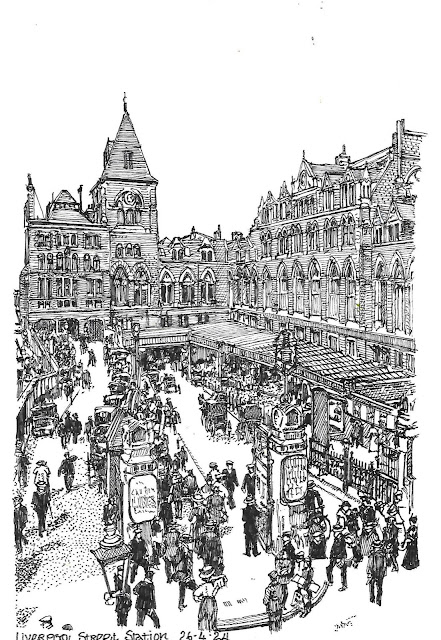

29) Liverpool Street Station

Here’s a

question for you to think about. In 1935, when Victor and Marjorie made their

scouting visit to London to work out which properties to use, which of the four

stations they picked was the busiest? Answer? Liverpool Street. How come? Well,

actually, between the two world wars, Liverpool Street was the busiest station

in the whole world.

Compared

with Kings Cross and Fenchurch Street, Liverpool Street was a relative

newcomer, first opening in 1874. If you’re wondering how it could be that the

London North Eastern Railway ended up with all of these termini in Central

London, well, none of them were actually built for the LNER. The LNER was only

14 years old when Vic and Marge first alighted at King’s Cross – previously the

terminus of the Great Northern Railway. Liverpool Street was built as the

terminus of the Great Eastern.

In his

book, “Britain’s 100 best stations” journalist Sir Simon Jenkins, who served on

the board of British Rail throughout the 1980s, described how Liverpool Street

came close to being demolished in the 70s. It survived not least because of the

energetic defence by the preservation movement, led by Sir John Betjeman, still

smarting from the demolition of Euston Station, which led to a public enquiry

in 1976 – 7.

Since then the station has been greatly redeveloped but sympathetically so. Every effort has been made to keep the character of the original station and has largely succeeded really well.

Park Lane. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the very famous

Frost Report Sketch, featuring John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett,

where the three of them stand in a line, and bowler hatted John Cleese says of

Barker ‘I look down on him because I am upperclass.” Barker then looks up at Cleese, then down on Corbett saying “I look up to him, but I look down on him.

I am middle class.” Ronnie Corbett then adds “I know my place.” Well, to me

Park Lane is like the Ronnie Barker character, and I don’t know whether I should

look up to it because it's in the most expensive set on the board or look down

on it because it is so clearly a second best to Mayfair. Not a heroic Scott of

the Antarctic second, nor a Buzz Aldrin second, either. Park Lane never has a

helpful Chance or Community Chest telling players to go to Park Lane. Park

Lane’s rent with a hotel might well be £1500, but that’s still a whopping £500

less than Mayfair. And Mayfair’s not even a street – it’s an area!

Park Lane runs from Marble Arch to Hyde Park Corner, and

this is where the name derives from. Before this it was called Tyburn Lane. The

Tyburn is one of London’s underground river, but as we saw when we visited

Oxford Street, Tyburn became synonymous with public executions. I can’t help

wondering if it’s the name of Park Lane that decided Victor Watson and his

faithful secretary Marjorie to put Park Lane exactly where it is on the board.

For where they put Park Lane on the London board there is Park Place on the

original Atlantic City Board. It must have seemed like a bit of a no-brainer,

especially considering that when they were out scouting Park Lane was already

one of the most prestigious locations in London. The fact that it was home to

the very swish newly built Dorchester Hotel can only have added to the

attraction.

Both of the properties in the purple set have had their

names used for cigarette brands. While we’re on the subject of Park Lane

trivia, being part of London’s inner ring road, along with Pentonville Road

Park Lane marks a boundary of London’s inner city congestion charge zone. Since

the start of the 20th century Park Lane has had a rather uncomfortable

relationship with motorised traffic. It officially reached saturation point in the 1950s, so work was carried out to widen the road between 1960 – 63 so that it has 3

lanes each way separated by a central reservation. This time also saw the

building of the largest underground car park in London, underneath Park Lane

and Hyde Park. I remember my father in the early 70s thinking about parking

there and taking us to see the Christmas lights, seeing how much the car park

cost, changing his mind and driving us all home again. Well, as he informed us,

it was the thought that counts.

Park Lane saw its ties with the worldwide game of Monopoly

when the Park Lane Hotel hosted the 1988 world Monopoly Championships. Bearing

in mind how long a game can take I wonder if it was finished in time for the

1989 championships. In the Sherlock Holmes short story “The Adventure of the

Empty House” the house in question is located in Park Lane. Now that’s one

achievement where Park Lane did come first. Mayfair has not held one yet!

Mayfair unlike all the other colour properties is not a street. It’s an

area, a rough quadrilateral – local resident, the Regency wit Sydney Smith called

it a parallelogram. It’s bordered by Park Lane, Oxford Street, Regent Street

and Piccadilly. Which, to add insult to injury, are all themselves locations on

the London board. I can’t help holding this against Mayfair. I can’t help

making an anthropomorphic comparison. To me, if Mayfair is a person, then it’s

a spoilt toff, who has everything handed to him on a plate, who wouldn’t last

five minutes in a dust up with Whitechapel or the Old Kent Road.

Coming back to reality for a minute or two, then, Mayfair takes

its name from a fair held in the area during the month of, well, May. The fair

predated the development of the area, first taking place during the reign of

Edward I. The fair lasted until 1764, specifically in the part of Mayfair that is

now called Shepherd Market – you can see the street sign on the sketch which is

based on a scene from the fifties, judging by the clothes.

As tended to be the case with other London fairs, the May Fair

became known for its increasing seediness, but the area took a remarkable turn

upmarket when the land on which it was held was obtained by the Grosvenor

family. The family would acquire the title of the Dukes of Westminster, a title

that is still in the family. They developed the land, building the elegant

Hanover Square, Grosvenor Square and Berkely Square. I’ve never heard a nightingale

singing there, but since I only walked through it at midday once that’s not

surprising.

Mayfair has not lost its exclusivity since its development

following the demise of the May Fair. The nature has changed, though. Prior to

the 20th century it was a London home to many aristocrats, but now there

are more commercial headquarters and national embassies – notably the American

embassy on Grosvenor Square.

I can’t help wondering whether Victor and Marge were swayed

in their decision to make Mayfair the most exclusive property on the whole

board by the presence of some very famous hotels. Brown’s hotel between

Albemarle and Dover Street is supposed to be one of the oldest in London. A.G.

Bell made the first telephone call in the UK there, and Rudyard Kipling wrote

at least part of the Jungle Book there. Even more famous is Claridges on Brook

Street. During the Second World War it was said that only Claridges was good

enough for exiled European Royalty.

Despite my chip on the shoulder about Mayfair, I have to

admit that it is a highly diverting part of London to walk around. It’s squares

are beautiful, the area is not short on sculpture – I like Hares by Sophie

Snyder in Berkely Square and there’s even a couple of museums – one to Michael

Faraday, and another in Brook Street dedicated to residents Handel and Jimi

Hendricks. What a musical collaboration that might have been.

No comments:

Post a Comment