What Should I Draw?

Whatever the hell you like! This is supposed to be fun,

remember! Most of us who love drawing aren’t trying to make a living from it.

Yes, alright, a lot of my art is for sale, but I’ve made a lot more money from

selling things that I wanted to draw and paint than I’ve ever done through

commissions. Bearing that in mind then, I would break it down into:-

Draw things that reflect your interests

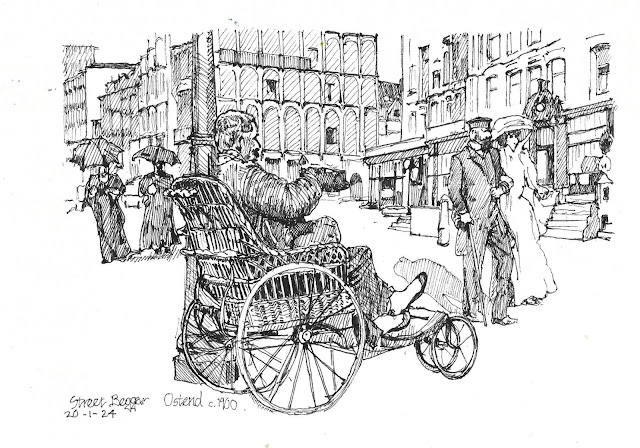

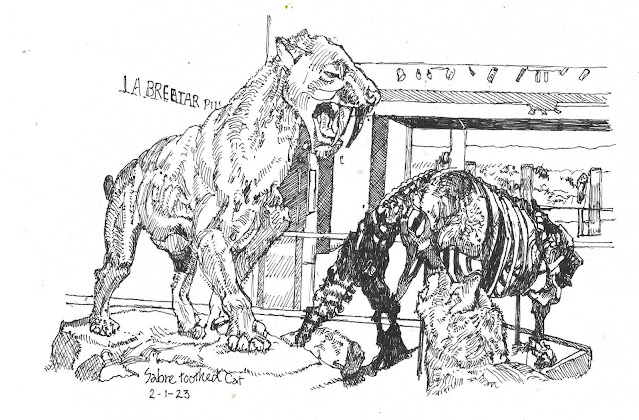

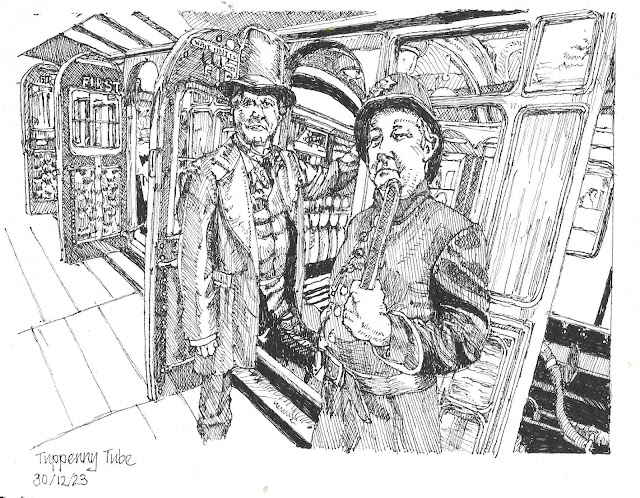

There’s a reason why the majority of sketches I’ve made so

far in my new sketch book are related to railways, Victoriana/Edwardiana,

London, architecture, and some fulfil several of these criteria. That’s because

I find these things interesting, and if you find something interesting then

you’re not going to mind spending time looking and drawing it.

Draw other artists’ work that you admire and which inspires

you

There’s a lot of benefit to be gained from copying others’

work. In the last couple of years I started copying some of Sir John Tenniel’s

illustrations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books. I love Victorian engravings I

general and Tenniel’s work in particular. This developed into a challenge to

copy all of his illustrations for the Alice books and that in its turn led me

to copying some of other artists’ later illustrations for the books. I wouldn’t

necessarily say that copying Tenniel has made me sketch more like he did.

However I feel I’ve learned a great deal about how he constructed these

wonderful pieces of work, and its hugely increased my appreciation and

understanding of his work.

Use prompts

When I undertook to make a drawing every day for 365 consecutive days, I found using the prompts from a Facebook group that I joined to be very helpful. Even if you don’t want to join a group, you could use Inktober prompts. Every October since 2009 the public have been challenged to make an ink drawing every day, post it somewhere someone else may see it (from social media to just sticking it on your own fridges.) Every year there’s a series of prompts for each day. You can google these. The challenge of sketching something which fits the prompt is a good one and well worth taking on, as it will lead to you drawing things you would otherwise never thought of drawing.

How long should I spend on a drawing?

On the surface this appears to be a ’how long is a piece of

string?’ question. Thinking about it, though, it’s a fair question. I think I

all depends on the reason why you’re making the drawing.

If you’re drawing in response to a prompt because you’re

trying to make a sketch every day for a specific amount of time, then you’re

limited in the amount of time you want to spend on it. There’s quite a few

quick exercises you can do in a practice session to help build your skills. For

example – pick a subject, then . . .

* Try to draw it in no more than three minutes. This is a

good warm up exercise

* Try to draw it in one continuous line without lifting your

pen/pencil from the page.

* Look at the picture for five minutes then try to draw it with your eyes closed.

* If you’re right handed then try drawing it for five minutes

with your left hand and vice versa if you’re left handed.

The purpose of this sort of exercise isn’t to produce

instant masterpieces but to loosen you up and get you focusing on the bare

essentials. It’s fun too.

Where and what you’re drawing can limit how long you have

to spend on a drawing too. I do as much urban sketching as I can, and to date

I’ve made urban sketches in about 20 different countries. Sketching from

life plein air is for me the ultimate

challenge. It’s at the same time the most challenging and also the most

rewarding kind of sketching. I don’t tend to spend more than an hour on an

urban sketch and this is necessary for a number of reasons. You’re out in

public and this means that people who are sooner or later going to get in your

way. If you’re out in the open then the light conditions are going to change

the longer you spend on the sketch. I suffer from arthritis and sitting, or

worse, standing for long periods becomes painful. Also there are places, for

example metro station platforms, where it’s not a good idea to stay sketching

for long periods of time.

I do sketch from photographs as well. This is a different

challenge to urban sketching. For one thing the camera has already done a lot

of the hard graft for you. The camera has translated a 3 dimensional subject

into a 2 dimensional representation. When you sketch from life you have to do

that yourself. There’s no imperative to sketch particularly quickly when you’re

sketching at home ad I’ve been know to leave a sketch and finish it off later.

As a rough rule of thumb I can do a very detailed sketch in no more than four

hours, which is about how long I spent on the dustman picture.