In the few weeks since I last posted, I've been concentrating on extending my range of Beautiful Britain prints. There's a couple of reasons for this. Firstly, as I'm sure that you know if you've been following the blog for any length of time, I just love drawing. In particular I love drawing buildings with a fineliner. Secondly, after a slow start, business in my Etsy shop has started picking up, so I wanted to extend the range of prints on sale.

So, here's the drawings from December so far: -

Brighton Pier. I did a mental inventory of cities in Britain, and I know that Brighton and Hove became a city maybe 20 years ago. My first thought was to do the Pavilion, and I may well yet end up sketching that. My second thought, though, as this, Brighton Pier. When I first visited it in the 70s, this was the Palace Pier, as compared to the derelict Victorian West Pier. Well, sadly the West Pier is now gone. but let's at least celebrate what we have left. I have actually painted this pier before (one oat of primer and two coats of whitewash guv, I thenk yow.) and sold an acrylic painting of it a few years ago.

Liverpool Roman Catholic Cathedral. I made a drawing of Liverpool's iconic Liver Building in the first set of beautiful Britain sketches. It has a drawback - it's not very good. I just didn't get it right. You can see it in my beautiful Britain gallery if you so desire - but it's not a drawing which is good enough to make prints of. So I really needed another drawing representative of the great city of Liverpool, and settled on this iconic building. Nicknamed Paddy's Wigwam, the Metropolitan Cathedral of Liverpool is a stunning modern building, opened during my lifetime in 1967.

Portsmouth Spinnaker Tower and Skyline. I see this on the horizon every time I drive to visit my mother who lives in Worthing. I don't think that I quite caught it, and this is one of the least successful of my recent drawings, in my opinion. Still, allow me to gloss over that by offering you a choice piece of trivia about Portsmouth. It is the only city in the UK o be completely built on an island.

St. Michael's Mount, Cornwall. Okay, not a city for once. I made a sketch of Mont St. Michel earlier this year, and thought that it's a shame that it's on the border between Normandy and Brittany in France, which means I can't include it in beautiful Britain. However, its sister establishment is in Cornwall, and this is it. I like this sketch - it came off for me, and I think that the shingle on the sides of the causeway works well.

Cardiff Bay. I have sketched - and painted similar views before. but I wanted to make sure that I included Cardiff, Wales' capital, in this sequence of drawings. I like Cardiff, and the Bay is terrific, and really well worth a visit if the opportunity ever presents itself to you.

Clifton Suspension Bridge.So, to the largest city in the West of England - Bristol. Let's be honest, when I was weighing up which landmark to sketch, it was always going to b this iconic bridge, designed by IK Brunel. Every time I have any reason to go to Bristol airport, I always drive under it. It's a beautiful bridge in its own right, but it's situation spanning the Avon Gorge means that it is nothing short of world class.

Edinburgh CastleYes, I've already sketched Edinburgh once, with a view from Calton Hill. But I just fancied having a go at the castle. What I like about this sketch isn't actually the castle, but the crags of the hill on which it sits.

Leeds Town Hall.

This is one of the buildings in the series that I have actually visited. On my first ever appearance on Mastermind, it was filmed in the Yorkshire TV studios in Leeds. (The following year, when I appeared again and actually won it was all shot in Manchester). I was blown over by this piece of baroque neo classical.

Now, having completed the drawing, I decided that, for the sake of variety, I'd have another go at applying a watercolour wash or two to an ink sketch. This was the result.

I have to say that I really rather like this. This is as close to what I was trying to achieve as I've ever got. I have to say, it actually looks better than this scan has made it - the colours aren't quite as washed out. Still. it encouraged me to have another go with the next drawing. Which was this one:-

The Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University. This is possibly Oxford's most famous landmark, forming part of the world renowned Bodleian Library. This is the plain drawing,

And this is the watercolour wash version. Again, I', not unhappy with the results, even though, again, the original does look a little bit better than it comes across in this scan.

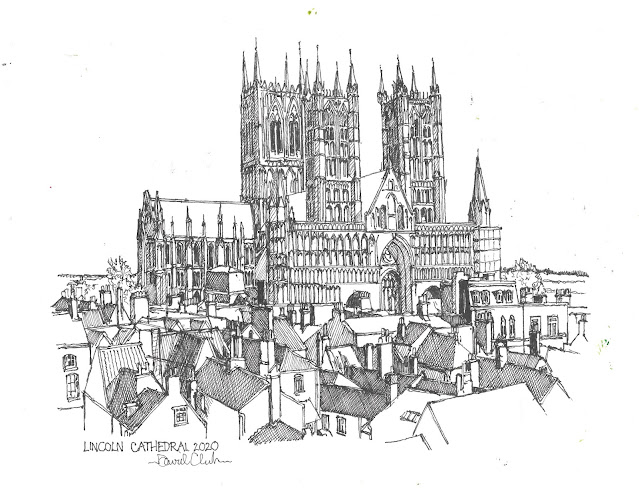

Lincoln Cathedral. This is the most complicated drawing I've made in December, and I simply haven't found time to apply watercolour yet. I guess hat Cathedrals are something of a fallback for me - if all other inspiration fails you can always go back to cathedrals - we have so many impressive ones. I think I once read that Lincoln Cathedral was, at one time, the world's tallest building, although I do stand prepared to be corrected on this one.

Finally, the sketch I made this morning, of the Roman baths in Bath.