Let’s start with a bit of context. In the summer I officially retired from being a teacher. Last Monday I started in my new proper job, a temporary position working in admin for the Community Dental Service, part of the NHS. I’m enjoying it a lot, however it does mean that I don’t have the time to draw and paint during the day and having been staring at a screen all day my eyes are too tired when I get home. So I haven’t made a huge number of pictures this week.

However, I have been looking more closely at the way that Tenniel’s successors have chosen to portray the Mad Hatter. Before that though, it’s worth noting that from his very first appearance of the Mad Hatter in Wonderland in Chapter VII – A Mad Tea Party, Carroll tells us what the Hatter says and what he does, but not what he looks like. Oh, and he never calls him the Mad Hatter either. He is first mentioned in the book when the Cheshire Cat offers Alice the chance to go one of two ways – one way she’ll meet a hatter, and the other a march hare, and he says that they’re both mad. The tea party doesn’t even appear in Carroll’s original manuscript “Alice’s Adventures Underground, so Carroll never illustrated him. So we have to start with Tenniel, and it must be fair to assume that Carroll was happy with the choices that Tenniel made. As always all of the illustrations on this page are my own freehand copies of the originals.

Despite never appearing in the original manuscript Carroll

must have liked the Hatter, for he brought him back in Looking Glass. Across the

two books Tenniel included the character in no fewer than 7 illustrations. In

Tenniel’s illustrations he is a small man with short limbs and an overly large

head. His most distinctive facial feature is his beakish overly large hawk

nose. He wears a large spotted bow tie, and a top hat which has a ticket stuck

into the band saying ‘In this style 10/6”. His hair is long and just a little

wild. As I said, Lewis Carroll wasn’t exactly backwards at coming forwards when

Tenniel did something he didn’t like with the characters so he must have been

happy with this visual representation.

Tenniel’s is the definitive depiction of the Hatter, so much so that subsequent illustrators have found it difficult to get away from it. I haven’t yet copied Arthur Ransome’s, yet I have copied illustrations by his contemporaries Harry Furniss and the Robinson brothers, Charles and Thomas. Here’s Harry Furniss:-

Harry Rountree also illustrated the Mad Hatter as early as

1908, and then again in 1928. The 1908 illustrations are sumptuous watercolours,

and in this edition the Hatter is clearly recognisable as a pretty close cousin

of what we’ve seen before. His top hat has a rounded top, but his nose is very

large. His concession to madness is having what looks like rolled up paper

cones in each ear. 1928’s Rountree hatter is facially pretty similar to the

1908 version. The hat is a true top hat, and to be honest although the

illustration is as technically well done as all of Harry Rountree’s work it

just seems to lack a little originality.

Coming forward to the immediate post war period, Mervyn Peake at least gives us something completely different from Tenniel. Or at least, almost completely different.

Mervyn Peake’s hatter has an overly large nose and his hair is rather wild but those are the only similarities he bears to Tenniel’s. I purchased a second hand combined copy of both Alice books with Mervyn Peake’s illustrations during the last week, and I’m bowled over by it. I’ve written before about how, as much as I adore Tenniel’s work, his illustrations to the books are sometimes a bit static and this is a criticism you just cannot make about Peake’s work. Peake’s hatter seems to wear a mad combination of hats of different styles and I love the way there seem to be plants sprouting out of the top of it.

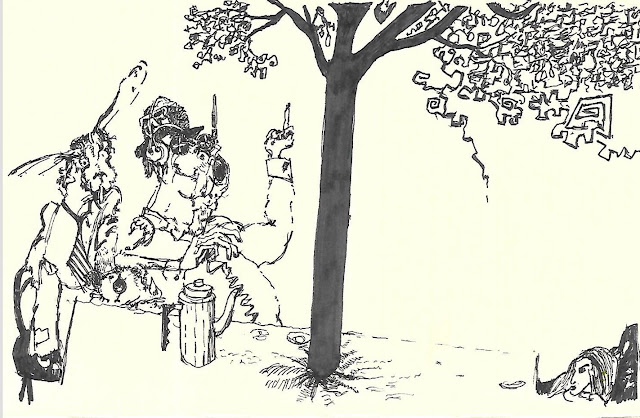

Ralph Steadman’s illustrations to both Alice books, from the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies are marmite to me – I either love them, hate them, or love them and hate them. I think his Hatter is in the last category. To me, the hare and the hatter look completely under the influence of some kind of narcotic – both are conspicuously smoking something and this is something that Lewis Carroll never wrote. The Hatter looks more animal than human here, although in other illustrations his face is more clearly human. Making this copy helped me appreciate the illustration more, but I can’t say that I really like it. But, it is without doubt something worlds apart from Tenniel. It’s interesting that Ralph Steadman chose to concentrate on the mad aspect of the character than the hatter. Nowadays we don’t have hatters any more. Maybe this is because of the association with Alice – we have milliners. The only concession to his profession with Steadman is what appears to be a bowler hat, and that is almost lost amongst headphones and other bits of headgear.

After the madness of Steadman’s Hatter it’s a relief to come back to the relative cosiness of Helen Oxenbury’s 1999 Hatter. As a whole set I find Helen Oxenbury’s illustrations really bring out the lightheartedness and fun in the books. Her Hatter is one of the smallest nosed depictions, and one of the fleshiest faced. He wears three of what looks like a cross between a trilby and a fedora, each perched on top of a slightly larger version. He also has the kind of moustache associated with a ‘spiv’ of the forties and fifties.

No comments:

Post a Comment