I’ve written a lot about Edgar Thurstan and the relationship between the 21 illustrations of the Alice books he made for the 1930 Odham’s combined edition, and the original illustrations by Sir John Tenniel. For me, as for many other lovers of the books, Tenniel’s illustrations are the vision that I see in my mind’s eye when I read the books again.

Why should this be? Especially when you consider that they

have a 1951 Disney animated movie to contend with. It can’t be just because

they came first , could it? Well, no, While I think being the first (published)

helped establish Tenniel’s rendition of Wonderland in public consciousness, if

they had been just mediocre they wouldn’t have lasted. And they’ve lasted

alright – boy how they’ve lasted.

I think we can find at least part of the answer by asking the

question – why did Lewis Carroll want Tenniel to make the illustrations in he

first place? Carroll doesn’t often get credit for this, but I think he really understood

how important illustrations would be for his story. He wrote it in manuscript

form as Alice’s Adventures Underground, and accompanied the handwritten text

with 37 of his own hand drawn illustrations, and presented it o Alice Liddell

for Christmas in 1863. When he conceived the idea of having the book published

he borrowed the manuscript and asked some literary friends to try it with their

children. They were very positive about the text, much less so about the

illustrations. Carroll, to his credit saw the recommendation to get a

professional illustrator for what it was. Good advice. He recognised what

Tenniel could bring to the party – the fact that he held off publishing Alice Through

the Looking Glass for several years until Tenniel could be persuaded to

illustrate it shows how essential he thought Tenniel was.

Why, though? Tenniel had already illustrated several books

prior to making the illustrations for Wonderland, but he was best known as a

cartoonist for Punch magazine. From 1850 he shared the duties of cartoonist

with John Leech – the illustrator of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, until becoming

sole cartoonist on the death of Leech in 1864. It seems that Carroll was drawn,

should you pardon the pun, to Tenniel through his great facility rendering

anthropomorphic animals, and his unusual habit of drawing from his prodigious visual

memory without using models or drawing from life. Did he perhaps see in Tenniel

a man capable of creating worlds out of his imagination?

I personally feel that Tenniel’s illustrations demonstrate

tremendous strengths. Namely –

Tenniel showed a fine ability to align his illustrations with

the text, both literally and metaphorically. Tenniel followed the story. His

illustrations show what Carroll wrote. In fact, he showed imagination in the

way that his illustrations linked physically with the text, particularly in the

L shaped illustrations of Alice looking up at Humpty and the Cheshire Cat, for

example. The two side of Alice passing through the looking Glass on opposite

sides of the page, and the two sides of the page showing the transformation of the

Red Queen into the kitten show great innovation.

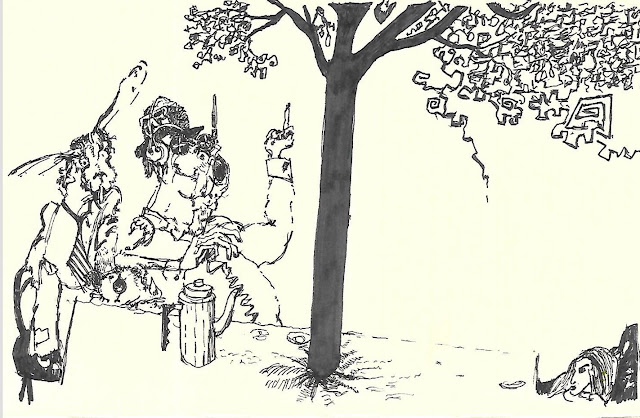

Tenniel managed to take what were sometimes sparse

descriptions of the characters’ appearance and create archetypes of these same

characters. A great example of this being the Hatter. (The Cheshire Cat tells

us that he’s mad, but Carroll always refers to him as just The Hatter). It’s

not an exaggeration to say that pretty much every depiction of the character since

has been influenced by Tenniel. Illustrators are faced with the stark choice of

borrowing aspects of Tenniel’s Hatter, or producing something that is

deliberately made to be as different from Tenniel’s as possible.

I think that at least part of what makes Tenniel’s work on the

Alice books so effective is that he doesn’t do sugar or saccharine. Even in the

illustrations for the earlier chapters of Wonderland, he never really gives us

anything cute, for want of a better word. Using monochrome with sometimes heavy

shading means that even his brightest illustrations have shadows. Add to this

his willingness to use relatively grotesque caricature. What Dickens achieved

with words with, for example, a character like Sarah Gamp in “Nicholas Nickleby”

Tenniel achieved with his drawing of the Duchess.

More than many of the illustrators of the Alice books who

would come later, many of Tenniel’s illustrations reward the viewer who takes a

second, more detailed look at them. While many who came after would concentrate

on characters while giving merely the hint of a background, there’s a real

richness to many of Tenniel’s backgrounds, especially the outdoors scenes. On

first glance you might not notice the glass houses behind the Queen of Hearts,

or the eel traps behind Father William when he is balancing an eel on his nose.

They’re here. They don’t strictly need to be there but they add texture. The

first time that you looked at the Duchess’ first illustration, did you notice the

smiling cat by her feet? It’s the Cheshire cat before he is even mentioned as

such.

I mentioned that Carroll seems to have appreciated Tenniel’s

facility with anthropomorphic creatures which you can see in his illustrations

of the fish and frog footmen. But he goes even further than just depicting

living animals as people. For Tenniel was s wonderful fantasy artist even

before anyone had conceived of that term. His sleeping Gryphon is a wonderful illustration,

while his jabberwock is nothing less than a tour de force. Personally I think

that this one illustration justifies the price of admission by itself.

--------------------------------------------

So, when you get right down to it I think that while other illustrators

may have illustrated parts of either novel more effectively than Tenniel did, I

think as a whole, as a set of illustrations they are unmatched. Which is ot the

same as saying that they are beyond criticism.

I’m not totally sure exactly how I feel about Tenniel’s

depiction of Alice. With her pinafore dress, and her long blond hair with its

eponymous Alice band, Tenniel gives us another archetype. Even an artist as

distinctive as Ralph Steadman gave us an Alice with the band, the hair and the

pinafore dress. My issue with Tenniel’s Alice is that there is not a lot of

life about her. Alice doesn’t do much more than standing or sitting listening

to and looking at other characters, or reacting to something. In some

illustrations she resembles a porcelain doll, and she’s about as dynamic as one

too.

This is a criticism you can extend to many of Tenniel’s

illustrations. In many of these his characters’ positions are beautifully

observed, but they are poses. We, the viewers are looking straight on at

characters who resemble actors who have been carefully placed in a tableau on

stage, and are holding perfectly still.

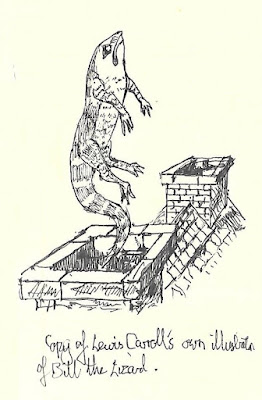

Of course, it’s a bit much criticising Tenniel for not

being more cinematic in his compositions when it was decades before cinema was

even invented. But it’s clear how static many of his illustrations seem when you

compare the slow and steady rise out of the chimney his Bill the Lizard makes,

compared with the explosive lizard expectoration in Harry Rountree’s depiction

of the same scene.

-

- -

Well, nobody’s perfect and trust me, it is far easier to

criticise than to do something that other people can criticise. To me, Tenniel’s

work is the standard against which all Alice illustrators must be judged. It’s

that simple.